Food Fights

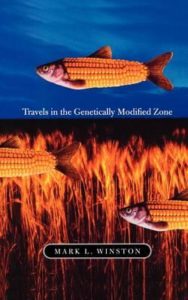

Review of

Travels in the Genetically Modified Zone

Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2002, 272 pp.

Like a bee pollinating a field of flowers, biologist and honeybee researcher Mark Winston spent more than two years buzzing around the twilight zone of agricultural biotechnology. This genetically modified (GM) terrain is a bewildering netherworld located somewhere between university laboratories and corporate board rooms, with compulsory detours to U.S. government regulatory agencies, Canadian canola farms, public interest group headquarters in a rural English village, and international patent and law courts.

What Winston found as he flitted about was, as Wonderland’s Alice would say, a landscape that became “curiouser and curiouser” the more he explored. It’s a world in which antibiotech leaders like Jeremy Rifkin try to highlight the inadequacies of the patent system by petitioning the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to approve a process to merge human embryos with embryos from an animal like a chimpanzee to create a kind of “humanzee.” It’s a not-too-distant universe in which genetically modified canola plants might produce anticoagulants for medical use, edible vaccines, and antibodies to fight against cholera and measles or the bacteria that cause dental cavities. And it’s a world that pits the science community against environmentalists, multinational corporations against organic farmers, and the technologically rich countries against the “gene-rich” but economically poor nations of the developing world.

This book is important because Winston, unlike many scientists, recognizes that resolving what some have called the Great GM Debate is not simply a matter of validating scientific data or assessing benefits and risks. His travels demonstrate that the public and policy battles over agricultural biotechnology and other scientific and technological marvels cannot be stopped by scientists telling Congress to “trust us” or by Ph.D.’s berating people for their lack of science literacy.

This book is important because Winston, unlike many scientists, recognizes that resolving what some have called the Great GM Debate is not simply a matter of validating scientific data or assessing benefits and risks. His travels demonstrate that the public and policy battles over agricultural biotechnology and other scientific and technological marvels cannot be stopped by scientists telling Congress to “trust us” or by Ph.D.’s berating people for their lack of science literacy.

In the high-stakes realm of science policy and corporate profits, Winston discovers that emotion, money, politics, religion, self-interest, and popular perceptions will always trump science. His book correctly observes that this food fight is not about potentially adverse health or environmental impacts from GM crops. It’s a battle over worldviews and over who decides winners and losers: in agriculture, consumer choice, environmental protection, business, and global trade.

Winston attempts to explore the full complexity of the GM controversy. He carefully dissects citizen and nongovernmental organization resistance, especially in Europe, to what most scientists see as beneficial herbicide-tolerant and pest-resistant crops. He meets many of the key players in this food fray, and he peels away all the main layers of their arguments.

What he rightly finds are serious flaws in the way society deals with scientific debate and new technologies. What he fears most is that the major actors in the GM debate do not have the foresight or resolve to improve the situation. And the real losers in this food fracas are the 800 million people currently suffering from hunger and malnutrition who consume less than 2,000 calories a day and who could benefit from biotech crops that promise to grow more food using less land, water, and pesticides.

Shouting match

Winston describes a highly polarized dialogue and dance of the deaf and blind. On one side sit arrogant companies who see only the advantages of GM food. Corporate executives will let nothing threaten or stand in the way of their hoped-for profits. He particularly faults industry for lobbying vigorously to maintain what the book calls a “regulation lite” approach to agricultural biotechnology: a patchwork system of lax government oversight that favors corporations and undermines public trust in the government’s ability to protect consumer and environmental interests.

Business resists any attempt to make what Winston sees as reasonable and, in the long run, self-interested regulatory reform. He is upset by corporate resistance to mandatory labeling for GM food and by industry opposition to shifting research about potential environmental safety and human health effects from company scientists to the public sector or independent laboratories. Winston believes such actions would shore up consumer confidence in the large-scale use of this new technology. Such reforms also would help lessen the cacophony of arguments by environmentalists that GM products are not sufficiently tested for hazards, such as the possibility that genes could jump from GM crops to wild plants and reduce biodiversity or create new superweeds.

Winston is equally hard on the community of nongovernmental organizations that sits on the other side of this unproductive shouting match. Although he acknowledges that protest groups have raised some important issues about GM crops, he faults them for often rejecting even the most rigorous regulation. He also accuses them of combating industry hype with “exaggerating risks, warping facts, and latching on to bad science.”

All sides, in his view, fail to deal with the scientific data objectively, and they foist on citizens a relentless barrage of sound bites and public relations stunts rather than a necessary platform for civil and informed dialogue and debate. He laments that in this environment it is impossible to decide what level of side effects from GM crops are worth the benefits. Winston feels that the negative impacts thus far range from nonexistent to slight to moderate. He notes that none of these effects are any worse than those caused by conventional agricultural practices, and that the reduced pesticide use possible with GM crops may be a plus for both the environment and human health.

In the middle of this free-for-all are well-intentioned scientists, employed by industry, regulatory agencies, and universities, who Winston nobly credits with wanting only to use their talents and skills selflessly in the pursuit of new knowledge and new technologies that will benefit humankind.

Too naively, in my view, Winston asks why all parties can’t just sit down and seek some middle ground that is guided by the facts and by the overriding public interest and common good. Why can’t each faction relinquish their shortsighted and destructive self-interests and opposing views for more rational civic discourse?

Democracy and capitalism are intrinsically messy, loud, and imperfect systems. They may be better than any of the conceivable alternatives, but they are never going to offer the rational utopian deliberation Winston is seeking. Human society is never going to operate like the highly focused and cooperative beehive Winston is more at home working with.

In looking for solutions to agricultural biotechnology’s dilemma –and to the public acceptance challenges facing any new scientific and technological development–Winston lets scientists off the hook too easily. He portrays scientists as well-intentioned pawns in white coats out of their depth in the halls of Congress, corporate America, and the media melee.

In my view, the science community is at the core of improved scientific debate and policymaking. Without greater involvement by scientists, there can be no solution to the GM debate or any reasonable management of contentious issues such as xenotransplantation, stem cell research, or nanotechnology.

According to a recent Sigma Xi and Research!America survey, 74 percent of scientists say they don’t have time to become involved in changing or supporting public policy, and 49 percent contend that they don’t know how to become involved. And although 41 percent maintain that their involvement makes no difference, only 14 percent affirm that they are happy with the policy-influencing job currently done by other scientists.

Scientists need to heed the long-proffered advice of leaders such as former presidential science advisor Neal Lane or the late Congressman George Brown. They must roll up the sleeves on their lab coats and become more involved in public policy and outreach, especially by pushing for some of the sensible regulatory change Winston advocates and holding politicians accountable for using science as a political football.

The regulatory problems Winston highlights are systemic and go beyond agricultural biotech: overreliance on corporate safety research, inadequate environmental impact testing, a jumble of multiagency oversight and responsibility, and often voluntary versus mandatory government compliance standards. No group has a bigger stake than scientists in developing an adequate regulatory framework and the independent research support capacity that will enable 21st-century science to move forward, yet at the same time address public concerns and put in place the safeguards necessary to mitigate or avoid potential risk.

As former House speaker and science champion Newt Gingrich called for in a speech to the American Association for the Advancement of Science: “Scientists must act as citizens. It is ridiculous to say that because what they are doing is noble and interesting that they should not also function actively as part of our society … If scientists truly believe that they are on the cutting edge of the future, they have a double burden because not only do they have self-interest, they also have the moral obligation of educating our democracy into creating a better future. Yes, citizenship is frustrating, but it is a privilege we must exercise. Yes, it means occasionally scientists will be involved in controversy. Yes, they have to learn communications skills such as speaking in a language everyone else in the room can understand. But these are doable things. They also are vital not only to the survival of this country, but to the future of the human race.”

Travels in the Genetically Modified Zone is a better book than Alan McHughen’s Pandora’s Picnic Basket (Oxford University Press, 2000), which presents the GM debate largely as a controversy created by popular ignorance of the science and facts behind GM food. But Travels is a less colorful and engaging book than National Public Radio technology correspondent Dan Charles’s Lords of the Harvest (Perseus Publishing, 2001), the other recent book tracing the development of agricultural biotechnology. But Winston is clearer and more explicit than either McHughen or Charles about some of the regulatory reforms necessary to create the kind of science and technology policy that will maintain public support for scientific and technological progress and allow important research to continue.

Winston is trying to go deeper into his subject than most. But he falls somewhat short of providing a true roadmap for what’s needed to bring about what British writer John Durant calls “socially sustainable” science and technology policy in the future.