Containing the fire

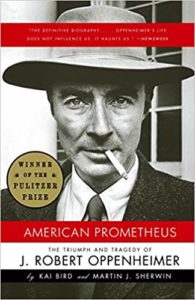

Review of

American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of Robert Oppenheimer

New York: Vintage, 2005, 721 pp.

Now that American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin has won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize, it is hardly necessary to say that this is a thoroughly researched, compellingly written, and extraordinarily perceptive book about one of the most gifted, successful, abused, and discussed scientists of the 20th century. And the story is about much more than what happened to Oppenheimer. It wrestles with the fundamental question of what role scientists should play in the making of public policy.

Now that American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin has won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Pulitzer Prize, it is hardly necessary to say that this is a thoroughly researched, compellingly written, and extraordinarily perceptive book about one of the most gifted, successful, abused, and discussed scientists of the 20th century. And the story is about much more than what happened to Oppenheimer. It wrestles with the fundamental question of what role scientists should play in the making of public policy.

Other good books have been written about Oppenheimer, but this is the definitive story. It benefits from all that has been written previously, as well as from extensive personal interviews and the emergence of information that became available after the publication of earlier books. It touches on Oppenheimer’s early education at the Ethical Culture School in New York City, his psychologically troubled 20s, his involvement in progressive political activism in the 1930s, his brilliant achievement with the Manhattan Project, his evolution into a major policy figure in Washington after the war, and the ruthless attack on his character conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission. Throughout, the authors pay special attention to Oppenheimer’s view of social responsibility and ethical behavior.

Although it is never possible to get to the bottom of what makes a person tick, anyone who has considered Oppenheimer’s life knows that the task is particularly difficult for someone whose brilliance touched on psychology and literature as well as science. Nevertheless, Bird and Sherwin do not avoid the challenge. Rather than ducking behind easy labels such as “enigma” or “man of contradictions,” they make perceptive and probing attempts to understand the processes by which Oppenheimer made the key decisions in his life. Of course, not all of Oppenheimer’s decisions would be considered wise when he made them, and many that appeared wise turned out not to have the desired or expected effect. Bird and Sherwin try to elucidate the logic behind all of Oppenheimer’s major decisions and to distill the lessons from his insights and his errors.

Oppenheimer’s story is a seminal case history for science policy. Before World War II, scientists had virtually no role in national policy debates. But that changed quickly and dramatically with the war. Mathematicians who could break codes became a valuable asset, and the development of radar was a revolutionary development in war fighting. However, the pivotal event was the recognition that physicists were acquiring the knowledge necessary to develop a bomb of unimaginable power. The possession of such a weapon could change not only the course of the war but also the dynamics of foreign policy for the foreseeable future. Suddenly, the fate of the nation and the world hinged on the work of a band of lab rats obsessed with the functioning of particles too small to see. Even more remarkably, the military standing of the United States was in the hands of a fragile-looking, soft-voiced left-winger who liked to quote Buddhist scripture.

The stunning success of the Manhattan Project cast a new light on scientists. These were heady days in which many scientists suddenly found themselves transported from the peaceful halls of academe to the bustling corridors of power. Scientists, particularly the physicists, understood that their newfound power and influence brought with them new responsibility. Many saw the bomb as their bomb, and they wanted a voice in how it would be used. But most scientists were outsiders to policymaking, and their inclination was to try to influence government from the outside with petitions and other entreaties.

Oppenheimer had a different view. As director of the Manhattan Project, he had more direct access to the nationÕs leaders. He didnÕt have to nail his petitions to the door; he had the option of walking through the door and participating in the councils of government. Activist outsiders such as the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard were skeptical of this strategy. They worried that one sacrificed his integrity when he entered the political world of compromise. Whether because he craved the power that came with being an insider or calculated that he would be more effective on the inside, Oppenheimer decided that he would influence government decisions as a participant rather than a protestor.

Oppenheimer understood that decisions about how to use the bomb would not be his alone, but he sacrificed his freedom to speak his mind publicly in order to participate in the decisionmaking process. Of course, he did not know what the president and his military advisers knew.He accepted their rationale for dropping the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but he later came to understand that this was not militarily necessary. Still, he decided to work within the system.

Oppenheimer famously said about the bomb itself that he had blood on his hands. The same could be said about his willingness to be the insider. He agreed to share responsibility for collective political decisions and thus shared the responsibility for decisions with which he did not agree. His best opportunity to shape the future of nuclear politics occurred soon after the end of the war.

Neils Bohr had talked to Oppenheimer in 1944 about the need to institute international control of nuclear technology, and Isidor Rabi reinforced this view in talks with Oppenheimer in late 1945. In January 1946, Oppenheimer learned that the world’s leaders were discussing the creation of a United Nations (UN) Atomic Energy Commission. President Truman appointed a committee chaired by Dean Acheson to draft a proposal for international control of nuclear weapons. Oppenheimer was named to a board of consultants chaired by former Tennessee Valley Authority chairman David Lillienthal. Oppenheimer argued forcefully for international control of military and civilian nuclear technology, and he convinced the committee. The resulting Acheson-Lillienthal report, written in large part by Oppenheimer, recommended the establishment of an Atomic Development Authority with far-reaching power extending from uranium mines to power plants to laboratories. Many of Truman’s advisors were skeptical about the plan because they worried that the Soviet Union could not be trusted. Bernard Baruch, who was given the job of selling the plan to the UN, was not enthusiastic. Nevertheless, he asked Oppenheimer to serve as his scientific advisor. Unhappy with Baruch’s ideas about how the plan should be altered, Oppenheimer did not take the job. Baruch went on to revise the proposal in ways that made it completely unacceptable to the Soviets, and it was rejected. Some of Oppenheimer’s friends criticized his decision not to join Baruch, because they thought Oppenheimer might have been able to change Baruch’s views. We cannot know exactly how this experience affected Oppenheimer, but after this, he worked hard to be included as a participant in government councils. He became chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission’s (AEC’s) General Advisory Committee and continued his campaign, begun while still at Los Alamos, to block the development of the far more powerful fusion bomb and to argue for greater openness and international control of nuclear technology.

Oppenheimer also learned that there are other risks in playing the political game. Lewis Strauss, his enemy on the AEC, became obsessed with his policy disagreements with Oppenheimer and devoted his considerable energy and cunning to destroying Oppenheimer. Strauss’s ruthless direction of the AEC hearing to review Oppenheimer’s security clearance led to Oppenheimer being stripped of his security clearance and expelled from the inner circle.

Some could derive from Oppenheimer’s fate the lesson that it is not wise to play with fire, but it would be a mistake to generalize from this one incident. Oppenheimer never said that he would have been better off remaining an outsider. He enjoyed his access to power, and he was right to recognize that one can have more leverage on the inside. There will always be people on the outside who can speak truth to power. Most of them will never have Oppenheimer’s option of entering the inner circle. But it is important for scientists to be part of that circle. They will not always win the day, and they should not always win the day. Government decisions must be guided by much more than scientific expertise.

When Oppenheimer learned in 1953 that he would have to face a hearing to determine, after 12 years of government service, whether he was a security risk, he had the option of simply resigning as a consultant to the AEC and avoiding the public ordeal of defending himself in what turned out to be a kangaroo court. Indeed, Einstein told him that the attack was so outrageous that he should simply resign. He could not understand why Oppenheimer would not simply turn his back on a country that would insult him so profoundly after all that he had contributed to it. But Oppenheimer was too loyal to his country to do that. Just as he continued to work within the government even though it did not take his advice, he decided that it was his duty to endure the hearing, to respect the processes of government, and to be as forthright as possible about his behavior. Tragically, he was crushed in the process, because his enemies had less respect than he for the rules and values of democratic government. The irony is that the man who was criticized by many of his colleagues for being too much of a pragmatist in working with government structures lost his last political battle because he acted the naïve idealist in a play written by the cynical power brokers.

Kevin Finneran (kfinnera@nas.edu) is editor-in-chief of Issues in Science and Technology.