Too much ado about testing

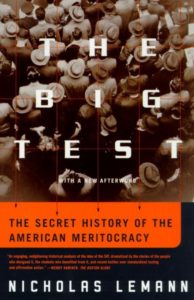

Review of

The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy

New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1999, 406 pp.

Nicholas Lemann, a staff writer for the New Yorker and the author of the outstanding history The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America, tells a fascinating story about the birth and growth of the Educational Testing Service (ETS) and its best-known product–the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT)–which high-school students take in the process of applying for admission to college. The personalities and events take on heightened significance in this account, because Lemann portrays the SAT as the gatekeeper for entry into the meritocratic elite that runs the country. A high score opens the door to the most selective colleges; then the top law and business schools; then the prestigious law firms, business consultancies, and government agencies. He wants the reader to be amazed that such an irrational and haphazard history could have produced an instrument of such unparalleled power. He is appalled that a three-hour exercise in filling in the dots determines who succeeds and who fails, and ultimately who determines the direction of the country.

Nicholas Lemann, a staff writer for the New Yorker and the author of the outstanding history The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America, tells a fascinating story about the birth and growth of the Educational Testing Service (ETS) and its best-known product–the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT)–which high-school students take in the process of applying for admission to college. The personalities and events take on heightened significance in this account, because Lemann portrays the SAT as the gatekeeper for entry into the meritocratic elite that runs the country. A high score opens the door to the most selective colleges; then the top law and business schools; then the prestigious law firms, business consultancies, and government agencies. He wants the reader to be amazed that such an irrational and haphazard history could have produced an instrument of such unparalleled power. He is appalled that a three-hour exercise in filling in the dots determines who succeeds and who fails, and ultimately who determines the direction of the country.

The problem with this story, however, is that the SAT doesn’t have this power. Who other than a handful of deluded psychometricians and a few overcompetitive 16-year-olds believes that the SAT determines the nation’s social hierarchy? Lemann should know better. The Mandarins (Lemann’s term) that rule the United States are not stupid enough to put that much faith in the hands of a test. The country is not run by a cabal of Mensa types with perfect SAT scores. College admissions committees know very well the limitations of the SAT. It is a moderately successful predictor of freshman college grades and is thus useful in combination with a number of other factors such as grades, recommendations, and activities in determining who will be successful in college. It might tell you that a student from a tiny religious school in Georgia is not only the best student in her class, but possibly one of the best students in the country. A very high score from a student with mediocre grades might convince a school not to admit that student.

The elite colleges do not select their students primarily on the basis of SAT scores; indeed, they like to boast about how many students with astronomical scores are not admitted. They recognize the importance of drive, resilience, leadership, and imagination. This is even more true in hiring decisions. Most high-school students understand that even a perfect score of 1600 does not guarantee admission to the school of one’s dreams and is obviously no assurance of eventual professional success. Lemann laments the existence of “a thick line through the country, with people who have been to college on one side of it and people who haven’t on the other.” That’s true. But there is no thick line between those who scored 1200 and those who scored 1400 on the SAT or between those who were admitted to Harvard and those who attended the University of Virginia or the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). The reality is that the overwhelming majority of colleges will accept anyone with a chance of graduating. The decision most closely linked to SAT scores is probably admission to a flagship state university. Admissions committees at state schools have less freedom than their counterparts at the private schools and must therefore give more weight to quantitative measures such as SAT scores. But does anyone believe that a student is barred from success by attending UCLA or San Francisco State instead of Berkeley? Some research has indicated that the right diploma makes a big difference in ultimate success. By tracking the histories of students and correcting for differences in SAT scores, high-school grades, parents’ income, race, and gender, researchers have concluded that those who attend more prestigious schools earn somewhat more. But recent research by Alan Krueger of Princeton University and Stacy Berg Dale of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation found that if one also takes into account other personal characteristics such as discipline, ambition, and maturity that are considered by admissions committees at the selective schools, the difference in the students’ eventual income virtually disappears. In other words, students with good grades, a high SAT score, and other desirable personal characteristics will be successful whether or not they attend the most prestigious institution. Besides, U.S. society is more random, more unstructured, and more wonderfully messy than Lemann admits. A gold-plated diploma doesn’t hurt, but it’s no guarantee of success, and academic credentials certainly don’t determine who is most successful or most powerful in this society.

The book’s title–The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy–suggests some nefarious conspiracy manipulating the social order. That’s too much heavy breathing for the story he tells. If anything, the test has enhanced social mobility and loosened the stranglehold that the New England aristocracy had on admissions to the Ivy League. As Lemann explains, much of the impetus for the use of standardized tests came from Harvard president James B. Conant, who saw testing as a way to replace some low-wattage rich boys with bright kids from less privileged backgrounds. But Lemann complains that on average the children of the wealthy and well-educated receive higher scores than the offspring of the poor and less educated. Is anyone surprised by this? The point is that many students from socially disadvantaged backgrounds do very well and gain access to high-quality college education. Conant also hoped that the talented and well-educated would use their talents and skills to serve the country. Lemann complains that too many just want to get rich. Is the SAT bad because Conant was unrealistically idealistic? The SAT expanded educational choices for a large number of young people from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds. That’s an achievement.

One curiosity of the book is that Lemann focuses almost exclusively on lawyers as the elite chosen by the SAT. The nation’s low regard for lawyers helps his argument. Many people believe that lawyers use their gifts simply to gum up the works. Frivolous lawsuits, meaningless court battles, and enormous financial settlements are of little value to the rest of us, so we don’t worry about whether law is attracting our brightest students. The reaction might be different if he focused on scientists, engineers, and medical researchers. We do want our best minds working on a cure for Alzheimer’s disease and designing airplane safety systems. The SAT is a far from perfect predictor of who will be successful in those endeavors, but I think that most people would prefer that we choose those with SATs of 1500 over those with SATs of 1000 to fill these jobs. We might even be grateful to have a test that helps identify those with the talent.

A bad rap

One reason why the SAT has received so much criticism in recent years is that it has done little to open doors for African Americans. The problem is that the average score of black students is about 200 points lower than the average white score, and blacks make up a disproportionately small percentage of those with scores of 1400 and above, who are the candidates for the most selective schools. And the problem is not that the SAT is not accurate for blacks. It actually overpredicts how well they will perform in college, and for blacks with high scores the overprediction is greatest. Blacks with SATs of 1000 get somewhat lower freshman grades than do whites with the same score. Blacks with SATs of 1200 have significantly lower grades than whites with the same score. Don’t shoot the messenger; the test is not the problem. The disparity in SAT scores indicates that the society has not been effective in developing black intellectual potential. Researchers have identified factors such as parent education, school funding, teacher expectations, and cultural signals that contribute to the problem, but they do not explain the whole gap. The SAT is telling us that more work needs to be done.

Although the book is written as a history, not as a policy analysis of standardized testing, Lemann does include an epilogue that sums up his perspective on testing and on the larger issue of the wisdom of meritocracy. He worries that we make decisions about an individual’s potential at too young an age, that the SAT is too narrow a measure of academic and professional potential, and that we are using the SAT to anoint a general elite rather than waiting and simply hiring the person with the best skills for each particular job. Finally, he wonders–impractically–why we can’t just provide everyone with a first-class education. The SAT score is not a life map, so the age of the test taker is not that critical. As a society, we make some decisions about education for young people at that age because not everyone will benefit from a Caltech education. We want to provide every young person with a high-quality education, but it does not have to be the same education for everyone. The SAT is a narrow measure, but that is why it is used in combination with other measures. We hope that employers have the good sense to fill jobs with those best able to do that job. Does there exist an employer who actually hires solely on the basis of SAT scores?

Finally, what undermines Lemann’s well-told story is his effort to make it a bigger story than it is. The birth and growth of the SAT is a compelling tale, but the secret power of the SAT in determining the social hierarchy is a nonstory.