“Real Policymaking Involves a Lot of Other Things Besides Pure Technical Analysis.”

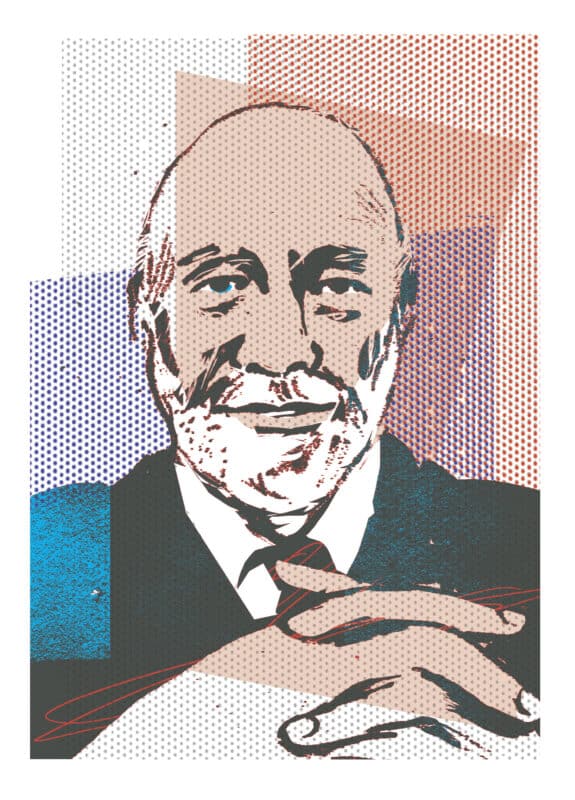

Nobel Prize-winning economist and former chair of the US Federal Reserve Ben S. Bernanke talks about the evolution of the Fed, the relationship between the United States and China, and transitioning from academic to policymaker.

Economist Ben S. Bernanke served as chair of the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2014, was one of three recipients of the Nobel Prize in economic sciences in 2022, and is currently a distinguished senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a member of the National Academy of Sciences. His new book, 21st Century Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve from the Great Inflation to COVID-19, traces the history of the Fed from the 1960s and ’70s through the pandemic. In an interview with Issues editor William Kearney, Bernanke discusses how the Fed has “changed remarkably,” the costs of economic decoupling of the United States and China, and the challenges for an academic who goes to Washington.

Do economists have a good understanding of how government can fuel innovation and how to measure the impact of that innovation?

Bernanke: Historically, the US government has been very important in supporting innovation through various kinds of incentives like tax credits, but also in commissioning or doing research on its own. For example, the internet and other important inventions had their roots in government-sponsored research.

The economic argument for government-sponsored research is simply that doing basic-level research that has wide potential benefits may not pay off for the private sector. A private company may not be able to capture the benefits of a breakthrough economically. So, going all the way back to the Manhattan Project, government has played a critical role in scientific advances and technological progress that are a major source of productivity increases.

The latest thing is artificial intelligence, and there’s a lot of speculation about what it means for productivity. History suggests that it takes some time for a new technology to become incorporated into private business and into the broader economy. We’ll see how long this one takes and how important it is, but over time you would expect a new technology like artificial intelligence to raise productivity and, ultimately, living standards.

Government has played a critical role in scientific advances and technological progress that are a major source of productivity increases.

Now, a new development recently coming out of the pandemic was a greater recognition that there are two goals that conflict to some extent. One goal is to have a global research environment where scholars and scientists can talk freely to anyone in any country and collaborate with scholars in other countries. From a purely scientific perspective, that’s the most productive way to go because researchers in your country get the benefit of what’s happening elsewhere and vice versa. The problem that governments are grappling with is that sometimes there could be national security implications of sharing advanced technologies with countries that might be rivals in the future. That has led to some attempts to try to limit sharing of research, ideas, and scientific collaborations across borders. Those two goals work against each other.

What is your assessment of talk of economic disentanglement between the United States and China?

Bernanke: There is some economic cost to disentangling, and then the question for politicians primarily is whether that economic cost is justified by the benefits for national security and autonomy. I think a complete disentangling certainly would be infeasible because of the many benefits of trade between these two economies. But how far it goes depends more on political and strategic considerations than it does on economics.

You brought up artificial intelligence. How do you think it will affect employment?

Bernanke: It’s an old question that goes back to the invention of the loom in the Industrial Revolution. Weavers in Great Britain were obviously unhappy, and understandably so, when their jobs disappeared in favor of automated weaving technologies. That is an issue.

On the other hand, despite tremendous improvements in technology and increases in productivity over the last few hundred years, we don’t have massive unemployment. So far, it seems that the best potential of artificial intelligence is to make existing professionals more productive—for example, to help doctors make more effective diagnoses and keep better track of medical records. New technologies have displaced some workers, but they’ve also created new jobs and they’ve made existing workers more productive. That’s the evidence from history, and we’ll have to see how this evolves.

In your new book you raise the question of whether reducing inequality and mitigating climate change should someday become goals of the Fed. Why so, and what might that look like?

Bernanke: I asked the question, but I don’t think the Federal Reserve is best placed to deal with those very important issues. On climate change, the Fed has some indirect influence in a couple of ways. One is that many PhD economists have some research experience in thinking about medium- and long-term effects of climate change on the economy. As bank regulators, they can examine potential costs to banks and their stability that might arise from either climate change itself or the policy responses to climate change.

So far, it seems that the best potential of artificial intelligence is to make existing professionals more productive—for example, to help doctors make more effective diagnoses and keep better track of medical records.

Climate change is a very, very big challenge. And the really big steps that are needed to avert climate change—such as developing new energy technologies and retrofitting old buildings and creating new infrastructure for electric vehicles—all those things are the province of the private sector or more likely the government. And by government, I mean broadly, like Congress. I think the Fed properly should focus most of its attention on its mandate, on the objectives given to it by Congress, which are full employment and price stability.

I think inequality is a similar issue in its complexity. The Fed is paying more attention to inequality and is monitoring unemployment rates across different groups. For example, during the pandemic the Fed appeared to put more weight on employment because of the benefits that has for people who are lower-income workers. But again, the Fed really only has one instrument—namely, financial conditions being tighter or easier and then promoting or slowing economic growth—and it can’t use that one instrument to achieve many different objectives at the same time. It can’t ease policy for one group and tighten policy for another group. It has to have the same policy for everyone in the country.

This is not to deny that inequality and climate change are first-order, very important issues politically and socially, but the Federal Reserve is just one agency, and it should focus primarily on the goals that Congress sets forth for it and the tools it has to achieve those goals.

The Federal Reserve has gone from a once-obscure institution to regularly being in the news, as you write in the book. How has it evolved in recent decades?

Bernanke: I was motivated to write the book by the fact that the Federal Reserve has changed remarkably since it was created in 1913. Those changes came about basically for two reasons: after the 2008 crisis, we needed new tools to stimulate the economy; and new players in the financial system meant our lending strategy had to evolve.

Very low inflation and a low underlying interest rate structure, starting around 2004, left the Fed with relatively limited space to cut rates to deal with economic slowdowns. When I was Fed chair, we cut the federal funds rate almost to zero in late 2008 amid the financial crisis—but the severe recession continued through 2009 and it was a slow recovery after that. So we needed new ways to stimulate the economy, which led to two principal tools. The first was quantitative easing [in which the Fed buys bonds and other financial assets to keep longer-term interest rates low, thereby stimulating the economy]; the second was forward guidance [to signal the likely direction of future monetary policy], which always existed to some extent at the Fed but became a much more central part of its toolkit.

The second change has to do with the fact that the financial system has changed since the Fed was created. Originally, banks and trust companies provided most of the credit in the economy. Since then, the financial system has evolved to include lots of other kinds of institutions to the point where banks provide less than half of all the credit that goes to Americans. The Fed was set up to provide liquidity and be a lender of last resort only to banks. And so the global financial crisis was a watershed moment because the crisis was most severe in the non-bank financial sector—what’s called shadow banks, including investment banks, various kinds of mortgage companies, and so on. The Fed had to develop a whole new set of tools to be a lender to other kinds of financial companies.

The Fed really only has one instrument—namely, financial conditions being tighter or easier and then promoting or slowing economic growth—and it can’t use that one instrument to achieve many different objectives at the same time.

That broadening of the Fed’s lending authority was revived in March 2020 when, under Chair Jerome Powell, there was a sharp financial crisis at the beginning of the pandemic. The Fed intervened very aggressively and very successfully. At the behest of Congress, the Fed set up some lending programs as backstops to the normal market functioning. That was very successful because it reassured investors and then private markets began to function again—which meant the Fed didn’t ultimately have to do much lending.

I would add a third dimension to how the Federal Reserve has changed, which is that it has become much more transparent and communicates a lot more to the public. I think the most obvious example of that is the chair’s press conference after every Federal Open Market Committee meeting. I am very proud of the fact that I was the first to do that.

As you say, the Fed has become much more transparent, but you conclude your book by saying that it will need to engage even more closely with all Americans. Why so?

Bernanke: Historically, the opening up of the Fed has been a slow process. There was a time when the Fed did not communicate much with anyone. That was a tradition among central banks going back to the eighteenth century probably. That began to change about 40 years ago, when central banks began to realize that providing more information about their intentions and plans could help align developments in financial markets with their own goals and strategies; that was what forward guidance was about.

But one thing the Great Recession showed was that the Fed, in the process of taking on more responsibilities, some of them controversial, also had a responsibility to explain what it was doing to the broader public and to get their feedback.

That serves a number of goals. One of them is simply democratic accountability. Another closely related goal is that if people understand the Fed and don’t think of it as some mysterious entity, they’re more likely to be supportive of Fed policies or at least to give them the benefit of the doubt.

One really good example of this is when, under Jerome Powell, the Federal Reserve was trying to develop a new monetary strategy. A very big part of that process was holding a series of what Fed officials called Fed Listens events around the country, where they invited not financial economists or financial markets participants, but rather representatives of various organizations including trade unions, civic organizations, senior citizens groups, and so on to talk about what the Fed does and how it affects them.

I think that was productive and sets the stage for where the Fed will probably go in the future. Given the important role that it and other central banks play in the economy, it’s becoming increasingly important that the Fed be open and be willing to engage. That involves a lot of speeches by Fed officials. It involves conferences that include non-economists. It involves testimonies and other types of communication that will get the word out through the media and directly to people who are not in the financial markets but are affected by Federal Reserve policies.

Do you worry about the Federal Reserve preserving its independence?

Bernanke: I always worry about that because the Fed takes on what might be, at least in the short run, unpopular policies. For example, Paul Volcker, one of my predecessors as Fed chair, came in with inflation at 13%, and he tightened monetary policy very dramatically and got inflation down quite quickly to about 4%, but the side effect of that was a sharp recession that took unemployment up to 10%. History would suggest that trade-off was the right thing to do because, following the conquest of inflation in the mid-1980s, until, say, 2001 when the internet bubble occurred, the US economy performed very well, and low inflation was one factor that allowed it to perform well.

Given the important role that it and other central banks play in the economy, it’s becoming increasingly important that the Fed be open and be willing to engage

Although we remember Volcker for his foresightedness in taking the actions that he did at the time, he was under huge amounts of political pressure. He received death threats. There were members of Congress who said they wanted to impeach him. Obviously, it was politically a very, very tough decision that he made. The Fed’s independence allowed Volcker to take the long-run perspective, which in our political system is not often the determining factor.

History shows that when central banks are independent and are not subservient to the executive, for example, inflation tends to be lower, and economic performance tends to be better. I think that is very important.

The Fed chairs make every effort possible to maintain the Fed’s independence, and I think that’s the flip side of the transparency. If you want to be independent, you need to explain what you’re doing and get feedback on what you’re doing, so that you’re not abusing that independence to do something that’s not in the public interest. Again, I think, to the extent that transparency promotes independence, that’s another reason for the central bank to be open and accountable.

What was it like to go from academia to chair of the Federal Reserve?

Bernanke: My academic research is on the effects of credit market disruptions on the macroeconomy, and I became Fed chair during a time when that was happening in an extreme case. So I would say that was an “on the one hand, on the other hand” type of situation.

If you want to be independent, you need to explain what you’re doing and get feedback on what you’re doing, so that you’re not abusing that independence to do something that’s not in the public interest.

On the one hand, my background as an academic provided me with a lot of knowledge and a lot of information that was helpful. When your research illuminates certain relationships or behavior of the economy, that helps you think about policy. And it helps to know history because it shows how others handled, or didn’t handle, previous crises.

On the other hand, academic analysis by its very nature tends to strip problems down into their simplest components. It tries to study relatively simple or straightforward examples of various phenomena. Real policymaking involves a lot of other things besides pure technical analysis. It involves politics. It involves working with colleagues. It involves dealing with enormous amounts of uncertainty. It involves dealing with imperfect data and models, so there are elements of judgment and interpersonal negotiations that are really not part of what academia prepares you for necessarily.

I think my background as a researcher, and as an academic, was essential to understanding the situation and to making good policy. But if it was necessary, it was not sufficient. It was also very important to understand issues like communication and cooperation, working with central banks from other countries, working with Congress, working with the president. All those things had to be learned basically on the job—and that’s why being a Federal Reserve chair is a very difficult job.