Dealing with terror

I was a member of John Hamre’s Commission on Science and Security, and he does an outstanding job in his article of explaining what we were about and why we made the recommendations we did (“Science and Security at Risk,” Issues, Summer 2002). However, we worked in a more innocent, pre-9/11 age. Our issue, balancing science and security in the Department of Energy’s laboratories and nuclear weapons complex, was much simpler than achieving a proper balance regarding bioterror weapons in the name of homeland security. Nuclear weapons are complex devices whose science is well known; the secrets are in the engineering and technology. Terrorists without a large-scale technical infrastructure would find it infinitely easier to buy or steal a nuclear weapon than to construct one based on breaches in our security.

Bioterror, after the anthrax letters, has raised justifiable fears that great damage can be done with biosystems that are much easier to make. Of all the potential weapons of mass destruction, bioweapons generate the most fear. At the time of this writing, universities are coping with the first attempts at controlling what biomedical research is done and who does it.

Physicists had to cope with a similar problem before World War II, but in a far simpler world. When the Hahn-Meitner paper on nuclear fission first became known, the nuclear physics community in the United States, which by then included many refugees from the Nazis, informally decided that it would be best not to publish work on fission so as not to advance Germany’s efforts any faster than U.S. scientists could move. The ban was voluntary and for the most part effective. Because the community was so small, word of mouth was sufficient to keep the entire community informed. Eventually, when the United States began a serious weapons program, the work became classified.

The biomedical community is too big and too dispersed to do the same thing effectively with potentially hazardous bioagents. Although biotechnology has the promise to advance our well being (and to make some people a great deal of money), the concern about bioterror is real, and I think it is likely that more controls will be imposed if the biology community does not take some action itself.

Such things as the recent synthesis of polio from its basic chemical constituents and a successful effort to increase the virulence of a smallpox-like virus raise a red flag to those concerned with limiting the potential for bioterror. I have to confess that I also wonder what was the point of these two programs other than sensational publicity. Might not the same science have been done with some more benign things?

I’m not a biologist, and so I have no specific answers on what to do. Once before, with recombinant DNA, biologists themselves devised a control system. It was not totally satisfactory, but it did block more draconian regulations while a broader understanding of the real dangers of recombinant DNA was developed. They need to do something like it again.

BURTON RICHTER

Paul Pigott Professor in the Physical Sciences

Director Emeritus

Stanford Linear Accelerator Center

Menlo Park, California

[email protected]

Transportation security

Layered security measures and curtains of mystery are keys to success in deterring and preventing terrorists, and they are also keys to restoring faith in and profitability to our nation’s transportation systems.

In “Countering Terrorism in Transportation” (Issues, Summer 2002), Mortimer L. Downey and Thomas R. Menzies wisely warn against trying to eliminate or defend every vulnerability in our systems, and they perform an important service in developing systems approaches. The analysis of single-point solutions and an overreliance on regulations is right on the mark.

I am more dubious than the authors about data mining and data matching as useful deterrents, although I believe trusted traveler and trusted shipper programs are important steps to take quickly. I am far more dubious about the ability of the new Transportation Security Agency (TSA) to accomplish the strategic role the authors envision. Their description of the creation of the agency by Congress is an all too familiar example of government responding to a crisis by cobbling together yesterday’s solutions and then issuing impossible and unfunded mandates for implementation. That’s no way to deal with tomorrow’s problems.

Immediately after the events of September 11, a group of us from RAND met with senior people in the Department of Transportation to offer without charge our research and analytic capability. We were told, “We aren’t yesterday’s DOT.” We left hoping they didn’t believe that; even more we hoped they didn’t think we believed it.

The point of the story is that government has never demonstrated an ability to put into place recommendations that would guard against tomorrow’s almost certain problems and thereby prevent their birth. For example, the White House Commission on Aviation Safety and Security (for which I was the staff director) made recommendations that might well have prevented one of the September 11 hijackings and deterred the others.

I believe that the strategic role the authors propose for the TSA cannot be accomplished by the current organization with the current staff and under the existing legislation. Departmental R&D programs are hijacked by appropriations committees at the behest of lobbyists, and departmental researchers have their conclusions overridden by policymakers whose minds are already made up.

An independent national laboratory for transportation safety and security seems to me a wiser solution. I propose that a university or university consortium run such a laboratory under the aegis of DOT rather than the TSA, which has its hands full implementing a very unwise piece of public policy.

The authors implicitly recognize the TSA’s shortcomings at the end of the article, where they place their faith in systematic and foresighted analysis in the yet to be created Department of Homeland Security. Again, I would argue that although everything the authors argue for and more needs to be done, it is unlikely to be done well within government. The new department will have its hands full simply organizing itself to do its immediate jobs, much less have the time and resources to look into the future.

There is a role for government, but it is not in keeping in house the analytic and research capability; it is rather in orchestrating the flow of resources to public and private researchers pursuing the most promising technologies and practices.

GERALD B. KAUVAR

Special Assistant to the President

George Washington University

Washington, D.C.

[email protected]

Safety performance and quality of security have long been important level-of-service variables for transportation systems. Safety considerations typically relate to errors in operations, judgment, or design of the transportation system, with no malice aforethought. Security considerations deal with overt, purposeful threats by human agents and have, of course, come into the public eye in the wake of September 11, 2001. Mortimer L. Downey and Thomas R. Menzies lay out a useful approach to dealing with this new level of concern with security issues. They recognize that “our failed piecemeal approach to security” has to yield to a more systems-oriented approach, built around the concept of layering. As they note, “A more sensible approach is to layer security measures so that each element, however imperfect, provides back-up and redundancy to another.” Just as generals prepare to fight the last war, not the next war, we often respond disproportionately to the most recent security threat without explicitly recognizing the systems approach that should be used in dealing with security issues. It is understandable that political impetus can push us to respond with zeal to the most recent event, but we must try to resist that if resources are not to be frittered away in what the authors call a “guards, guns, and gates” approach.

Ensuring a secure transportation system in the face of terrorist threats is a daunting task, and, of course, the devil is in the details. Translating the useful philosophy of layered security into an action plan is a far from trivial undertaking. Designing a layered approach against terrorists who have shown themselves to be quite willing to die in the process of their acts is a job of extraordinary complexity. Downey and Menzies have laid out the framework for approaching these issues through collaboration, research and development, and information sharing. But, of course, the specifics will be critical to a successful approach.

Finally, a view beyond the scope of the Downey and Menzies paper: Any approach to antiterrorism must have a component that deals with destroying the ability of terrorists to operate. Our best minds may produce a layered system of greatly enhanced security, but unless we greatly reduce the capacity of terrorists to carry out their violence in the first place, we will be dealing with only part of the problem. A systems approach should necessarily include terrorist capacity reduction; in a sense, it is one more layer.

JOSEPH M. SUSSMAN

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, Massachusetts

[email protected]

Memories: True or false?

As remarkable as Elizabeth Loftus’s evidence of memory fallibility is, I find even more remarkable the utter lack of evidence for memory repression: the pathological inability to remember something that otherwise could not be forgotten (“Memory Faults and Fixes,” Issues, Summer 2002). I am open to the possibility of its existence, but I urge its proponents to follow the following 10 rules–four “do’s” and six “don’ts.”

The do’s are straightforward, if often ignored: prove the event occurred, prove the subject witnessed the event, prove the subject lost memory of the event, and prove that only repression could explain the forgetting. In doing this, avoid the following six traps.

Do not claim that truth does not matter. Psychoanalyst Michelle Price once wrote, “Although the need to determine the truthfulness of claims of child abuse may appear rational and reasonable in a court of law, it becomes highly suspect in a psychotherapy/psychoanalytic context.” Truthfulness is much more than “rational and reasonable” in both law and science.

Do not rely on fiction as scientific evidence. Although fiction is a great illustrator of truth, it is rather poor evidence of truth. One repression advocate referred to Hitchcock’s Spellbound as if it demonstrated repression. Psychiatrist Harrison Pope observed that the idea of repression did not occur in literature until shortly before Freud began to write about it.

Do not accept evidence as proof of repression unless other explanations are ruled out. Psychologist Neal Cohen described Patient K, who was electrocuted while repairing his oven. When K regained consciousness he thought it was 1945 instead of 1984 and could not remember anything occurring in between. Cohen attributed K’s amnesia to psychological stress. Seems to me a physical explanation was more likely. (The man was fried!)

Do not vilify skeptics. Psychiatrist Richard Kluft once wrote, “In this series, there were no allegations of alien abductions, prior lives, or similar phenomena that inspire knee-jerk skepticism in many scholars.” Knee-jerk skepticism? How else should we respond to tales of alien abductions?

Do not distort clinical reports. A recent treatise on memory repression and the law described a patient who recovered a repressed memory of his mother’s attempted suicide. The original report, however, includes several facts making the anecdote much less compelling. The patient was schizophrenic, with a lifelong history of memory dysfunction. It is not clear from the report that he really witnessed the attempted hanging or, if he did, that he ever forgot about it.

Do not omit material details. A clinical psychologist reported “a verified case of recovered memories of sexual abuse.” The patient was sexually abused by her father in childhood, as corroborated by her older sister. The clinical report suggests that as an adult the patient repressed her memory of the abuse (which, we should observe, would have been several years after the trauma occurred). But in subsequent correspondence with the author I learned that she discussed the abuse with her husband before marrying him. This sounds much more like a memory that waxes and wanes in salience than a case of verified repression.

ROBERT TIMOTHY REAGAN

Senior Research Associate

Federal Judicial Center

Washington, D.C.

[email protected]

Elizabeth Loftus describes her interesting research on the malleability of memory and details the practical consequences of this work for several contentious issues in society in which the veracity of memory reports is of crucial importance. My own research on memory illusions, as well as the work of other cognitive psychologists, leads to similar conclusions. However, Loftus has been the foremost public spokesperson on these issues and frequently speaks out in the courtroom as well. She is to be congratulated on her public stands, in my opinion, although they have caused her personal grief.

One criticism frequently leveled at Loftus’s research is that it occurs under “artificial” (that is, laboratory) conditions and may not apply well to the real-world settings to which she wishes to generalize. After all, the argument goes, Loftus usually tests college students; the materials used in her experiments are not the life-and-death scenarios of the outside world; and the experiments lack many emotional elements common for witnesses to cases of child abuse, rape, etc. These arguments are all true, as far as they go, but I have come to believe that they are all the more reason to marvel at the powerful findings Loftus obtains.

Many critics fail to understand that the nature of experimental research is to capture one or a few critical variables and manipulate them to examine their role in determining behavior, while holding other variables constant. The crucial point is that Loftus shows her strong effects on memory under the relatively antiseptic conditions of the psychology laboratory and by manipulating only one or two of many possible variables. For example, in her studies on the effects of misleading information given after witnessing an event, participants usually are exposed to the erroneous information only one time, yet large effects are obtained. In the real world, such misleading information may be given to a witness (or retrieved by the witness) many times between the occurrence of a crime and later testimony in court. Similarly, the manipulation of other variables in the lab is often a pale imitation of their power in the outside world. In realistic situations, many factors that are isolated in the lab naturally co-vary and probably have synergistic effects. Thus, a witness to a crime may repeatedly receive erroneous information afterwards, may receive it from several people, and may be under social pressure from others (say, to identify a particular suspect). These and other cognitive and social influences that are known to distort memory seem to increase in power with time after the original episode. As retention of details of the original episode fades over time, outside influences can more easily manipulate their recollection. All these influences can operate even on individuals trying to report as accurately as possible. If anything, Loftus’s laboratory studies probably underestimate the effects occurring in nature.

Another criticism sometimes leveled at Loftus and her work (in some ways the opposite of the previous one) is that it is unethical: She is manipulating the minds of her participants by using memory-altering techniques. However, she does so in situations approved by institutional review boards, using manipulations much weaker than those existing in nature. Nonetheless, she still produces powerful effects on memory retention. It is ironic that some therapists who criticize Loftus on these ethical grounds may themselves produce much more powerful situations to encourage false recollections in their practice, and with little or no ethical oversight.

Loftus’s research, like all research, is not above reproach, and astute criticism can always improve research. However, the questions of whether Loftus’s research can be applied to outside situations and whether it is ethical can, in my opinion, be laid to rest.

HENRY L. ROEDIGER III

Washington University in St. Louis

St. Louis, Missouri

[email protected]

False confessions, false accusations, malingering, perjury, problematic eyewitness perception, and fallible memory are not new to society or law. They are human problems that we impanel juries to resolve with the aid of expert testimony and with the requirement that a person making an assertion has the burden of proving it. Elizabeth Loftus is correct in saying that we should always be vigilant against mistaken claims. For that reason, we must examine her own position for errors. Unfortunately, there are many, only a few of which can be addressed here.

Loftus believes that what she calls “repressed memory” is a dangerous fiction, and she believes that science supports her view. In fact, it does not. Approximately 70 data-based scientific studies have appeared in the past decade, using a variety of research designs, specifically addressing the issue of repressed memories of childhood sexual abuse, and there are more studies addressing dissociative amnesia for other disasters, such as war trauma, rape, and physical abuse. Although most people remember trauma, and indeed are afflicted with those intrusive memories, in some people the mind walls the memories away from consciousness as a defense mechanism until a later period of time. The American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV, which sets the standard of care for all psychiatrists and psychologists, recognizes the legitimacy of repressed memory under the term “dissociative amnesia.” Logicians tell us that to prove the existence of a class, you need only demonstrate the existence of one member of that class. Ross Cheit has documented many cases of dissociative amnesia and childhood sexual abuse, including corroborated criminal cases involving priests (see www.brown.edu/Departments/Taubman_Center/Recovmem/Archive.html). The Oxford Handbook of Memory (2000) is surely correct in stating that although “the authenticity of discovered memories was originally treated as an either/or issue . . . , recent discussion has become more balanced by promoting the view that while some discovered memories may be the product of therapists[‘] suggestions, others may correspond to actual incidents . . . A number of cases, documented by the news media and in the courts, have provided compelling corroborative evidence of the alleged abuse.”

Loftus’s sole emphasis on memory error masks the stronger evidence regarding memory accuracy for the gist of events. She points to her numerous studies on the “post-event misinformation effect,” but what she does not report is that in her studies, which use a research design most favorable to her conclusion, more than 75 percent of the subjects resist her efforts to alter their memories of peripheral details. Studies with more sophisticated research designs have found a memory alteration rate of only 3 to 5 percent. Thus, for peripheral details, which are easier to influence than the “gist” of an event, the overwhelming majority of test subjects resist memory alteration (false memory implantation). Furthermore, Loftus’s laboratory experiments do not mirror real-life trauma, and, for obvious ethical reasons, they only involve attempts to implant false memories of minor details that have no emotional significance to the subjects. There is a marked difference between whether a person saw a stop sign or a yield sign and whether a person experienced sexual molestation.

Loftus treats hypnosis at arm’s length and with distaste. In fact, however, she makes several logical errors and does not accurately reflect the science. First, she generalizes from the fact that hypnosis can be abused to the conclusion that it will always be abused. Second, she confuses the use of a technique with the misuse of that technique. Third, she addresses the wrong problem. With memory retrieval, the contaminating factor is whether the interviewer is supplying suggestive misinformation. The problem is not whether the subject has been hypnotized. In fact, numerous studies, some by Loftus herself, clearly show that the same suggestive effects occur without hypnosis. In one such experiment, she reported that she was able to alter a memory in some people by asking how fast were the cars going when they “smashed” as compared with when they “hit.” No hypnosis was involved, simply the use of a leading question. If the hypnotist does not use leading questions or suggestive gestures and does not supply the content of the answers, pseudomemories cannot be created. Fourth, she provides no evidence, because there is none, that hypnotically refreshed recollection is more apt to be in error than memory refreshed in other ways. Fifth, the studies most frequently cited to condemn hypnosis have involved the very small percentage of the population who are highly hypnotizable. Even with this most vulnerable population, however, implanting false memories of nonemotional details is rejected by about 75 percent of the subjects. It is not hypnosis that may contaminate memory; it is any interviewer who supplies suggestive misinformation.

There are many horror stories recited in Loftus’s paper about false memories and/or false accusations. It is equally possible, however, to recite many instances of true memories and true accusations from real sexual abuse victims. There are also many true stories about therapists whose lives have been harmed by lawyers trying to make huge profits using false memory slogans. But reciting cases is not the important point. Emotional stories and selective citation may be rhetorically persuasive, but they are the enemies of science. Loftus concludes that the mental health profession has harmed true victims of childhood sexual abuse. But she does not explain how her rejection of repressed memory and strong emphasis on why memories of abuse should not be believed helps them. Indeed, as she is well aware, survivor groups do not view her as their friend.

When prosecutors seek to obtain an indictment, they must present their evidence to a grand jury without the defense having an opportunity to state its case. Several years ago, a man summoned to grand jury duty asked to be relieved of that responsibility because he could only hear in one ear. The judge denied the request, wryly observing that the man “would only be hearing one side of the case anyway.” Loftus has told only one side of the case, leaving out all of the evidence and science that disagrees with her. In the very brief space I have been allotted, I have tried, in the words of radio commentator Paul Harvey, to tell “the rest of the story.”

ALAN W. SCHEFLIN

Professor of Law

Santa Clara University School of Law

Santa Clara, California

[email protected]

Universities and national security

In “Research Universities in the New Security Environment” (Issues, Summer 2002), M. R. C. Greenwood and Donna Gerardi Riordan discuss the need for “the free flow of information” in research, the involvement of more U.S. students in science, and greater breadth in national research priorities.

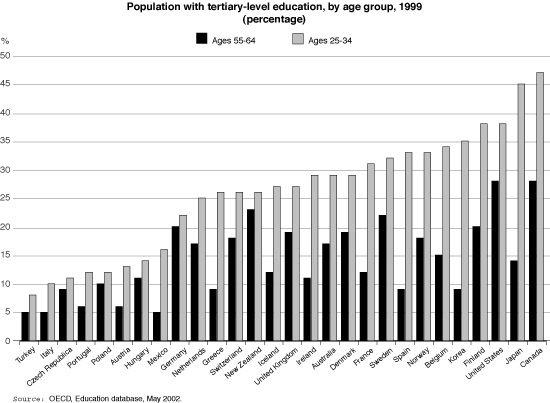

The fundamental principle of science is the free interchange of information. The open (and hence peer-reviewed) nature of U.S. science is a reason for its preeminence internationally. Thus a shift, as the authors point out, from a “right to know” to a “need to know” violates this prime directive of openness. A second advantage of the traditional openness of U.S. universities is the attraction to them of many international science and engineering students. Current events require a tempering of this influx, which will require care. America’s closest recent attempt at scientific suicide has been our unwillingness to put sufficient resources into educating our own citizens who might enter science and engineering. Our ethnic minorities are underrepresented in science and engineering; they are overrepresented in the U.S. military by 50 percent (source: Department of Defense report on social representation in the U.S. military for fiscal year 1999). Through national indolence, we have not adequately attracted this obviously loyal pool of U.S. citizens into science and engineering. One could couch the authors’ suggestion for a revival of the earlier National Defense Education Act as a way to produce the science warriors needed for the post-9/11 world.

The authors dub the current federal support of science as “missiles and medicine.” Vannevar Bush’s 1945 letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt included health, wealth, and defense as the targets for federal support. The omission in current federal policy is a key one. As Lester Thurow points out, “Put simply, the payoff from social investment in basic research is as clear as anything is ever going to be in economics.” An obvious example of the omission of “wealth” and of Thurow’s point is in the computer field, where defense concerns caused the creation of large mainframe computers, but an emphasis on wealth enabled the creation of personal computers and the World Wide Web.

The key word in this article is “collaboration.” Large societal problems require big research teams, which are perforce interdisciplinary. A largely ignored aspect of post-9/11 is the crucial role of social science. As Philip Zimbardo, president of the American Psychological Association, said at the November 2001 meeting of the Council of Scientific Society Presidents, “Terrorism is a social phenomenon.” How can social scientists best be included with engineers, linguists, theologians, and others in post-9/11 efforts?

The authors point out the need for many types of collaborations in areas such as addressing large societal issues and bringing academia and the federal government together to set research priorities. Effective processes are needed to enable these collaborations. At the University of Kansas, our Hall Center for the Humanities is creating a series of dialogues between representatives of C.P. Snow’s “two cultures,” with the goal of encouraging large-scale collaborations for academic research. How can large-scale multidimensional projects be carried out? What are enabling processes to this end?

ROBERT E. BARNHILL

President, Center for Research, Inc.

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas]

[email protected]

M. R. C. Greenwood and Donna Gerardi Riordan address three areas of great importance–information access, balance in our research investments, and foreign students–and present a proposal for action. (In the interest of full disclosure, I should mention that I came to this country as a foreign student in 1956.)

The article is an important contribution to the lively debate about such issues that has arisen after 9/11. In addition to hearings in Congress and meetings arranged by the administration, the debate has involved such important constituencies as the National Academies (a workshop, a report, and planned regional meetings), the Council on Competitiveness (including a forthcoming national symposium), a number of professional societies (notably the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology), educational associations (including the American Association of Universities), and much of the rest of the research university community.

The debate needs to focus on increasingly specific questions. We cannot answer with generalities the intricate questions of priorities, balance, tradeoffs, and cost effectiveness that present themselves as we define the nation’s research agendas, long-term and short-term, and grapple with how to ensure appropriate security.

One point that was made with considerable force at the National Academies’ workshop on post-9/11 issues in December 2001 was that we must build on existing structures and processes to the greatest extent possible. To be sure, we need to continue to assess the needs and weaknesses in our system that 9/11 revealed, and take remedial steps. But this is not a time, as was the case during World War II, when we need to establish a whole series of new crash programs to meet the nation’s needs. It is incumbent on us in the higher education community to be as specific and persuasive as possible in making the argument for the need for, and effectiveness of, specific investments rather than speaking in general terms about the need for greater investments. We have to be prepared to participate in a vigorous debate about priorities and means.

The authors make the important point that we need to develop the nation’s linguistic and cultural competencies as well as its scientific ones. This is one area where the higher education community has the responsibility for making the case. It would be useful to think about this issue in terms of three different needs, even though the programs required in each case may well intersect.

First, the nation needs to develop a much larger group of experts with linguistic and cultural competency for specific government tasks. Most of this group will likely be government-trained in government programs.

Second, and at the other extreme, we need to greatly enhance the effort devoted in K-12 and undergraduate education to provide our citizens with better knowledge and understanding of the linguistically and culturally diverse world in which we live and about the complications that entails, even extending to deadly results. A heavy responsibility rests on us in the higher education community to do this, regardless of government investment, and certainly without having the government tell us how to do it.

Third, there is a need for an expanded category of academic specialists in many languages and cultures who can do research and teach in such specialties.

The authors propose the establishment of a counterpart to the National Defense Education Act prompted by Sputnik. Maybe we need such a framework to address needs both in the sciences and in the humanities, but creation of such a program will depend on the demonstration that meeting each need is a critical aspect of an overall security whole. In any case, I think we need to address the issues in something like the terms I just outlined. Such specificity should help us make the points we need to make.

On the information access issue, I wholeheartedly endorse what the authors have to say. The widely recognized effectiveness of the U.S. system of higher education and research is due in considerable measure to its openness. But since there are legitimate security concerns, we need to continue our debate in very specific terms to ensure that the restrictions that may be necessary are both reasonable and effective.

NILS HASSELMO

President

Association of American Universities

Washington, D.C.

[email protected]

Control mercury emissions now

For over a decade, the utility industry and regulators have actively debated whether it is appropriate to control mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants, and if so, to what extent. Matt Little’s recent article, “Reducing Mercury Pollution from Electric Power Plants” (Issues, Summer 2002), neatly frames the debate by describing the myriad of issues that will likely affect its outcome. One point, though, warrants emphasis: that reducing mercury pollution nationwide is not only the right thing to do to protect public health and wildlife, it is feasible.

A vital part of our food supply is contaminated with mercury, and in 2001 we learned from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention its effect on the U.S. population: One in 10 women of childbearing age is eating enough mercury-contaminated fish to put their newborns potentially at risk for developmental harm. Such compelling evidence should have automatically translated into a national call for action to reduce all human sources of this toxic contaminant. Unfortunately, this hasn’t happened.

Although the federal government has moved forward with regulating several major sources of mercury pollution, efforts to further delay controls on power plants are ongoing. State governments, on the other hand, are cracking down on mercury pollution much more comprehensively by targeting consumer and commercial products, including cars; the health care industry, including dentists; and electric utilities.

All the evidence is in hand to make an informed decision with respect to regulating mercury emissions from electric utilities. 1) Mercury poses a real, documented threat to our future generations and to wildlife. 2) It is technically feasible to control mercury from coal-burning plants (even from plants that burn subbituminous and lignite coals, as has been recently demonstrated by utility- and government-funded studies). 3) Control is cost effective, with estimates likely to continue their downward trend as the demand for control technology increases. 4) Control is essential if we anticipate burning coal in the coming decades to meet our electricity needs, which we do.

Electric utilities should not be allowed to continue to shield themselves behind false claims that there is neither adequate scientific evidence of harm nor the technical know-how needed to set strict standards. Mercury pollution is pervasive in the United States and globally, and efforts need to be made on all fronts to eliminate this problem. The time is long overdue.

FELICE STADLER

National Policy Coordinator

Clean the Rain Campaign

National Wildlife Federation

Washington, D.C.

[email protected]

Matt Little’s excellent and comprehensive article on mercury pollution exposes one of many weak points in the Bush administration’s so-called “Clear Skies” proposal. The legislation would be a giant step backward in air pollution control and would enable irresponsible corporations to continue to evade pollution controls. Indeed, so bad is this industry-friendly legislation that it was very quietly introduced on the eve of the congressional summer vacation by Rep. Joe Barton (R-Tex.), who quickly slinked out of town rather than try to defend the plan to reporters.

Regarding mercury, the current Clean Air Act will require each electric power plant in the nation to curb mercury emissions by as much as 90 percent by 2008 and then to further limit any unacceptable mercury risks that remain. The administration bill would repeal these requirements, substituting a weak national “cap” that would not be fully implemented before 2018 and would allow at least three times more mercury pollution. [In the fine print, the legislation would require that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) work closely with the coal-friendly Department of Energy on a cost-benefit analysis to see if EPA should require more than a minimal amount of mercury reduction.] There is little question that the electric power industry can meet the 90 percent mercury reduction standard in the competing legislation drafted by Sen. Jim Jeffords (I-Vt.). Jeffrey C. Smith, executive director of the Institute for Clean Air Companies, testified before Jeffords’ committee in November of 2001 that the 90 percent standard could be met even by plants that burn low-sulfur coal.

The real question here is whether coal-state politics–the Bush administration’s desire to keep such coal states as West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee in the “red” column in 2004–will triumph over public health protection. Public health concerns were exacerbated in late July 2002, when a Food and Drug Administration panel recommended that pregnant women limit their consumption of tuna fish because of the mercury threat to fetuses.

Will our lawmakers choose to protect coal and power industry profits or public health?

FRANK O’DONNELL

Executive Director

Clean Air Trust

Washington, D.C.

[email protected]

Matt Little’s article hits the nail on the head. Not only is mercury pollution control becoming increasingly affordable and efficient, but recent research also indicates that we would benefit from stricter controls sooner.

Our public health is at stake. Recent Food and Drug Administration action added tuna to their consumption advisory for women of childbearing years and children. When toxic pollution reaches levels requiring people to limit their consumption of a normally healthy, commonly consumed food, it’s obvious that action is overdue.

Mercury’s toxic effects go further than direct human health effects. Mercury’s effects start with mammals, birds, fish, and even soil microbes. Recent peer-reviewed research links mercury pollution to increasing antibiotic resistance in harmful pathogens. This and other recent research indicate we have an incomplete but sufficient understanding of mercury’s toxic effects on the world around us to warrant action.

Utilities remain the largest source of uncontrolled mercury emissions. Yet there are workable options to reduce this pollution. Technology taken from other pollution control applications combined with an understanding of combustion chemistry makes mercury control feasible and affordable. As Little points out, the Department of Energy is years ahead of its schedule to find cost-effective reductions in mercury emissions at levels exceeding 90 percent of those currently emitted.

We are making progress on issues raised by utilities regarding the contamination of the waste stream due to mercury control. The use of waste heat, in a process similar to retorting, holds promise for removing mercury from potentially marketable products as is done with wallboard produced from lime used in sulfur control. Also, by moving mercury control processes to follow particulate controls, we’ve resolved the problem of carbon content in ash. When we sequester mercury from ash and other by-products, not only do we ensure this mercury won’t come back to haunt us, we also offset pollution control costs by creating safe, saleable products.

We need to look at multiple pollutant approaches that help solve our current and potential future problems. Although no single technology has yet been developed that totally controls mercury, coal-fired power plants don’t produce mercury pollution as their only air pollutant. Everyone, including utilities, agrees that we eventually need to reduce carbon emissions. Increasingly, utilities realize that pollution control, when aggregated and considered in the context of multiple pollutants, is affordable.

As a courageous start, Sen. Jeffords’ Clean Power Act (S.556) recognizes solutions. Coal use will continue for years to come as we increase energy supplies from cleaner, cheaper, and safer sources. While this occurs, we need to protect our families and our future from mercury’s toxic legacy. With the understanding of control technologies, the knowledge about mercury’s effects, and the free market to drive results, the capacity for solutions is evident.

ERIC URAM

Midwest Regional Representative

Sierra Club

Madison, Wisconsin

[email protected]

Needed: Achievement and aptitude

In “Achievement Versus Aptitude in College Admissions” (Issues, Winter 2001-02), Richard C. Atkinson discusses the SAT I and II tests. But to say whether aptitude or achievement should be used as the criterion for university admission is too simplistic.

As an Admissions Tutor in Britain 15 years ago, I had a very simple aim: to admit students who had the capability to succeed in the course. To do this, we tutors looked at available evidence, including but not limited to examination results, using strategies that were adjusted to the subject.

In my particular case, chemical engineering, I looked for people who had knowledge of chemistry and aptitude in mathematics. The former was necessary so that they could understand the lectures from day one. The second was so that they could learn new tricks. At that time, school subjects were done at O (ordinary) and A (advanced) levels. When a student had not taken a subject at A level, the O-level grade could be used as some guide to aptitude but was a much lesser achievement.

Other subjects were different. Law basically required high grades at A level in any subjects. The degree assumed no prior knowledge but required clever people. To take a degree in French, you had to be fluent in that language (via A level or any other means). You could start studying Japanese or Arabic, providing you had already learned another foreign language (Welsh was acceptable).

In general, A level grades were found to be a fair predictor of success for some subjects studied at both school and university and a poor predictor when the degree was very different in style and/or content from the school subject.

For most subjects, motivation was important. People who had visited a chemical plant, attended law courts, been on an archaeological dig, done voluntary work in hospitals, published articles in the school newspaper, or had any other involvement in their chosen subject: These were the ones who demonstrated an interest.

Things are no longer so sensible for British Admissions Tutors. Government interference and the power of information technology have pressured tutors to offer places only according to grades on standard examinations. Woe betide the tutor who makes allowance for a student who was ill or came from a deprived background. Damnation upon the tutor who refuses a place to a student with the right number of points but lacking other essential qualities.

Students in higher education need some achievement, some aptitude, and some motivation for their course. These can be traded off to some extent: I have seen hard work overcome both lack of ability and lack of prior knowledge, but never simultaneously. However, the balance is likely to vary significantly from subject to subject.

MARTIN PITT

Chemical and Process Engineering

University of Sheffield

United Kingdom

[email protected]

New approach to climate change

“The Technology Assessment Approach to Climate Change” by Edward A. Parson (Issues, Summer 2002) deals with an extremely important issue that has direct implications not only for the mitigation of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions but also for adapting to climate change. However, I think it is overstretching the point to say that policy debate on global climate change is deadlocked because the assessment of options for reducing GHGs has been strikingly ineffective. Surely, if there is a deadlock, it is due to a much larger body of reasons than the single fact identified by the author. Perhaps Parson has a point in saying that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has failed to draw on private-sector expertise. At the same time, the analogy that he draws with the Montreal Protocol is, by his own admission, not entirely valid. Take, for instance, the case of the transport sector. Undoubtedly, the widespread use of technology that is being developed today for private vehicles and the possible enlargement of a role for public transport in the future would have a major impact in reducing emissions. But is industry in a position or willing to provide an assessment of the evaluation of future technology, the costs associated with specific developments, and how their use would spread in the economy? We are not dealing with the narrow issue of finding replacements for ozone-depleting substances. The changes required to reduce emissions of GHGs would involve changes in institutions, the development of technology at prices that would facilitate change, and perhaps some changes in laws and regulations and their implementation.

I also find it difficult to reconcile the certainty that Parson seems to attach to the assessment of technological and managerial options with his contention that “future emissions and the ease with which they can be reduced are much more uncertain than the present debate would suggest.” He goes on to explain that this uncertainty stems from imperfectly understood demographic, behavioral, and economic processes. If such is the case, then certainly the assessment of future technology, which is necessarily a function of demographic, behavioral, and economic processes, also suffers from a similar level of uncertainty. The assessment of technology, particularly as it relates to future developments, is not as simple as implied in the article. Nor can the analogy between the implementation of the Montreal Protocol and mitigation options in the field of climate change be stretched too far.

Having said so, I would concede the point that the IPCC and the assessment work it carries out would benefit greatly from interaction with industry. There is no denying the fact that the understanding of technology and the factors that facilitate or inhibit its development are areas that industry understands far better than any other section of society. No doubt, several members of the academic community who study technology issues can carry out an objective analysis of the subject without the undue influence that may arise out of narrow corporate objectives and interests. This community of academics, however, is generally small, and smaller still is that subset which works closely with industry and is qualified to provide advice to industry in shaping corporate policies for technology development. There is, therefore, much to be gained by interacting closely with industry on technology issues, because even if one does not get direct inputs that can go into IPCC’s assessments, there would be much to gain through a better understanding of technology issues, which industry is well qualified to provide.

The suggestion made by the Parson, therefore, about the IPCC following a technology assessment process similar to that used for ozone-depleting chemicals is largely valid. Should industry be able to spare the time of people who have the right knowledge and talent, a substantial body of material can become available for the authors involved in the IPCC assessment, which can help improve the quality of sections dealing with technology. It would, of course, be of great value to involve industry experts extensively in the review process for the Fourth Assessment Report. Through this letter, I would like to express the intention of the IPCC Bureau that Parson’s article will receive a great deal of attention, and the spirit of his suggestions will be implemented; even though the precise details of his critique and advice may be difficult to incorporate in practice.

RAJENDRA K. PACHAURI

Director General

Tata Energy Research Institute

Delhi, India

Chairman, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

[email protected]

Edward A. Parson is to be commended for identifying the many lessons from the Montreal Protocol Technology and Economic Assessment Panel (TEAP) that can improve the important work of the comparable Working Group 3 of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC WG3).

By the time the first IPCC technical review was organized, TEAP had been in operation for more than five years and had earned a reputation for consistently reporting technical options allowing the Montreal Protocol to go faster and further. As insiders in the Montreal Protocol and TEAP, we can confirm Parson’s key conclusions, offer additional insight and emphasis, and suggest a way forward.

Parson correctly describes TEAP membership as respected industry experts guided by chairs who are primarily from government. Over 75 percent of the 800 experts who have served on TEAP are from industry, whereas 80 percent of IPCC WG3 members are government, institute, and academic scholars.

Critics of a TEAP-like IPCC approach argue that a majority of industry experts could manipulate the technical findings. Parson debunks these skeptics by showing that TEAP’s technically optimistic and accurate findings speak for themselves. Balanced membership, clear mandates, strenuous ground rules, personal integrity, decisive management, and proper committee startup achieve objective assessment.

Legendary United Nations Environment Programme Executive Director Mostafa Tolba created TEAP and nurtured it to strength before it faced governments. Tolba knew that the best scientific experts are in academia and government programs such as the British Antarctic Service, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and the World Meteorological Organization. But Tolba also knew that the best technical experts on alternatives to ozone-depleting substances are in businesses such as AT&T, British Petroleum, Ford, Nortel, and Seiko Epson, and in military organizations. Industry participation in TEAP makes the reports more accurate, more visionary, and more credible, while government and academic members ensure that the reports are not biased.

So what is the way forward? We suggest reorganization and collaboration. Reorganization to welcome industry participation and allow technical panels to write reports based on expert judgment and cutting-edge technology. And collaboration of TEAP and IPCC on topics of mutual interest, such as hydrofluorocarbons and perfluorocarbons, which are important alternatives to the ozone-depleting substances controlled by the Montreal Protocol but are included in the basket of greenhouse gases of the Kyoto Protocol.

If your appetite is whetted, consult our new book Protecting the Ozone Layer: The United Nations History (Earthscan, 2002) for the “‘what happened when,” Parson’s new book Protecting the Ozone Layer: Science and Strategy (Oxford University Press 2002) for the “‘what happened why,” and Penelope Canan and Nancy Reichman’s new book Ozone Connections: Expert Networks in Global Environmental Governance (Greenleaf, 2002) for the “what happened who.”

STEPHEN O. ANDERSEN

K. MADHAVA SARMA

Andersen ([email protected]) is a founding co-chair of TEAP and pioneered voluntary industry-government partnerships at the U.S. EPA. Sarma ([email protected]) was executive secretary of the Secretariat for the Vienna Convention and the Montreal Protocol from 1991 to 2000.

It is sad to see serious academics such as Thomas C. Schelling (Issues, Forum, Winter 2001) defending President Bush’s rejection of the Kyoto Protocol. The crucial point is that Bush refused to give any consideration to the problem of global warming and made it clear that the United States would do nothing to control the emission of CO2. He even refused to accept the conclusions of the scientists studying the issue, thus resembling the president of South Africa, who denied the relation of HIV to AIDS.

It is suggested that September 11 changed everything and now Bush is a great leader in the war against terrorism. Unfortunately, as Bush prepares an attack on Iraq, more and more people realize that whether it is the issue of “terrorism” or the Kyoto Protocol, the one thing of importance to Bush is oil.

LINCOLN WOLFENSTEIN

University Professor of Physics

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

[email protected]

Managing our forests

I have little argument with the idea that we should test new approaches to decisionmaking for the national forests. However, I find Daniel Kemmis’ arguments (“Science’s Role in Natural Resources Decision,” Issues, Summer 2002) less convincing, and they do nothing to justify his faith in collaboration.

Kemmis implies that the 19th century Progressive movement made science the alpha and omega of Forest Service decisions. That was not so in the agency’s early years, nor has it been since. The agency’s first chief, Gifford Pinchot, was a pragmatic and masterful politician; he knew when to compromise. For example, he explained his decision to allow grazing on public lands this way: “We were faced with this simple choice: shut out all grazing and lose the Forest Reserves, or let stock in under control and save the Reserves for the nation. It seemed to me but one thing to do. We did it, and because we did it . . . National Forests today safeguard the headwaters of most Western rivers.”

On July 1, 1905, Pinchot sent employees the “Use Book,” describing how the national forests were to be managed. It said that, “local questions were to be settled upon local grounds.” He hoped that management would become science-based, and he established a research division. He knew that all management decisions were political acts and that all decisions were local.

I served in the Forest Service for 30 years, including 3 as chief, and never knew of a management decision dictated solely by science. Decisions were made in the light of laws, regulations, political sensitivities, budgets, court decisions, public opinion, and precedents. However, using science in decisionmaking is both wise and mandatory. Using science implies ensuring the quality of the science involved. Certainly, courts insist that their decisions meet the tests of application of science and public participation.

Collaboration is neither a new concept nor a panacea. Kemmis might have noted that, unfortunately, many collaborative efforts of the past decade have failed, wholly or in part, and others remain in doubt.

As an ecologist and manager, I define ecosystem management as nothing more (relative to other approaches) than the broadening of the scales involved (time, area, and number of variables), the determination of ecologically meaningful assessment areas, and the inclusion of human needs and desires. To say that ecosystems are more complex than we can think (which is true) and are therefore not subject to management (which is not) makes no sense. We can’t totally understand ecosystems, but we manage them or manage within them nonetheless, changing approaches with new experience and knowledge. So, management by a professional elite based totally on good science is a straw man that has never existed.

Kemmis would replace the current decisionmaking process with collaboration, in which he has great faith. Faith (“a firm belief in something for which there is no proof”) is a wonderful thing. I suggest that, in the tradition of the Progressive movement, such faith is worthy of testing and evaluation. We agree on that.

JACK WARD THOMAS

Boone and Crockett Professor of Conservation

University of Montana

Missoula, Montana

Thomas is a former chief of the U.S. Forest Service.

Smart mobs is veteran tech-watcher Howard Rheingold’s term for the growing ranks of people linked to each other through the mobile Internet. In the millions worldwide today, mobile devices could start outnumbering personal computers connected to the Net as soon as a year from now. When that happens, says Rheingold, paging or phoning and “texting” won’t simply be easier; almost unconstrained by location, the combination will also unlock new possibilities for socializing, doing business, and political networking.

Smart mobs is veteran tech-watcher Howard Rheingold’s term for the growing ranks of people linked to each other through the mobile Internet. In the millions worldwide today, mobile devices could start outnumbering personal computers connected to the Net as soon as a year from now. When that happens, says Rheingold, paging or phoning and “texting” won’t simply be easier; almost unconstrained by location, the combination will also unlock new possibilities for socializing, doing business, and political networking.

Beyond College for All reexamines the school-to-work transition for those who do not go on to further education after high school. In particular, it focuses on the connections and contacts made (or not) between students, employers, and high schools, documenting the considerable confusion and lack of information among these parties. The book also examines the nature of the contacts made between employers and high schools and what types of information are sought and shared among schools and potential employers. The focus is on the United States, but the book also discusses possible lessons learned from Japanese school-to-work transition programs. As a result, it provides readers with a one-stop reference written by one of the leading scholars on this topic.

Beyond College for All reexamines the school-to-work transition for those who do not go on to further education after high school. In particular, it focuses on the connections and contacts made (or not) between students, employers, and high schools, documenting the considerable confusion and lack of information among these parties. The book also examines the nature of the contacts made between employers and high schools and what types of information are sought and shared among schools and potential employers. The focus is on the United States, but the book also discusses possible lessons learned from Japanese school-to-work transition programs. As a result, it provides readers with a one-stop reference written by one of the leading scholars on this topic.

This book is important because Winston, unlike many scientists, recognizes that resolving what some have called the Great GM Debate is not simply a matter of validating scientific data or assessing benefits and risks. His travels demonstrate that the public and policy battles over agricultural biotechnology and other scientific and technological marvels cannot be stopped by scientists telling Congress to “trust us” or by Ph.D.’s berating people for their lack of science literacy.

This book is important because Winston, unlike many scientists, recognizes that resolving what some have called the Great GM Debate is not simply a matter of validating scientific data or assessing benefits and risks. His travels demonstrate that the public and policy battles over agricultural biotechnology and other scientific and technological marvels cannot be stopped by scientists telling Congress to “trust us” or by Ph.D.’s berating people for their lack of science literacy. Suppressing fire was the stated policy of the U.S. Forest Service for much of the past century and still dominates the thinking of most voters and legislators. Its consequence has been to increase the amount of fuel (incendiary plant material) in forests, preventing minor fires but making huge ones like those that were in the news during the summer of 2002 more likely.

Suppressing fire was the stated policy of the U.S. Forest Service for much of the past century and still dominates the thinking of most voters and legislators. Its consequence has been to increase the amount of fuel (incendiary plant material) in forests, preventing minor fires but making huge ones like those that were in the news during the summer of 2002 more likely.