When Art Catalyzed Both Community and Treatment

Ivy Kwan Arce is a Chinese American activist and artist. Diagnosed as HIV positive in 1990, she has fought for HIV/AIDS causes with AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), Treatment Action Group, People With AIDS Health Group, Asian Pacific Islander Coalition on HIV/AIDS, and God’s Love We Deliver. She fought for access to medication, clinical trials, and prevention measures such as pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. As a federal HIV and AIDS Planning Council member from 1995 to 1999, she distributed Ryan White Title I funds to patients. A Whitney Biennial 2022 featured artist, she is married with two HIV-negative children.

Kwan Arce was invited to curate a collection from the archives of Visual AIDS, an organization that uses art as a “catalyst to engage public response, dialogue, and scholarship around HIV/AIDS.” The following is an excerpt from her statement accompanying that collection, named 最初, lxs primerxs, 第一, the firsts.

My HIV-positive diagnosis was in 1990. I was infected in 1989. I am documenting my experience by focusing on the first wave of people with AIDS (PWA)—my guiding lights—who became the first public servants by choice, courage, and destiny. They fought for survival and expanded solutions for AIDS as well as other diseases like cancer and COVID-19. Here is the work of some of the individuals I knew and those I didn’t, but whose lives and work shaped my odds.

The PWAs who were part of the first wave formed organizations and support groups such as ACT UP and Treatment Action Group. These organizations brought people together, provided a sense of community and empowerment, and pushed government and science to develop solutions for long-term survival and prevention.

I am documenting my experience by focusing on the first wave of people with AIDS (PWA)—my guiding lights—who became the first public servants by choice, courage, and destiny.

The invitation to curate for Visual AIDS gave me an opportunity to dissect that period of my life. Although early public and government messages around AIDS said that only a few people were being affected and were generally in the gay male community, there were other first responders doing work that saved lives, prevented infections, and created new pathways to change science. In sharing those connections, I am extending the footprint of their unique, brave legacies.

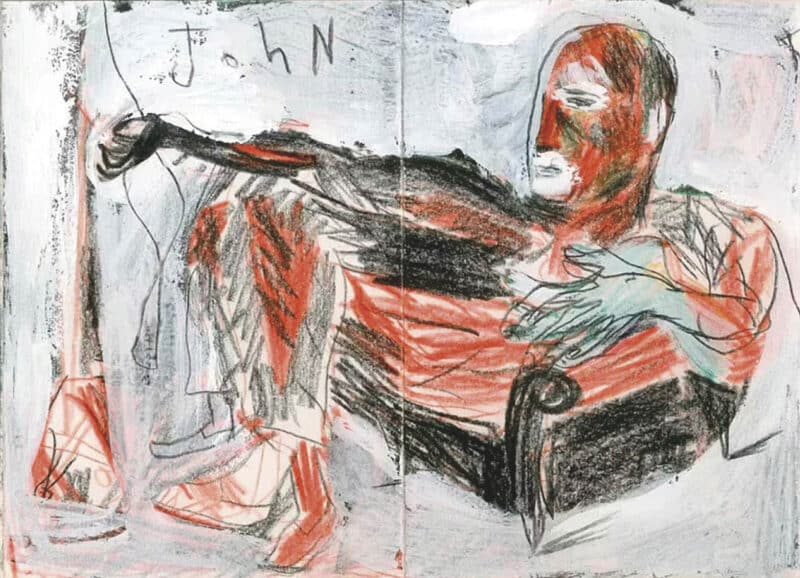

The first HIV-positive person I met was Antonio Lopez, when he did an illustration workshop at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California, where I was a student. I had heard during the workshop that Antonio had AIDS—“that thing that Rock Hudson had.” I did not really know what that meant because Antonio looked “normal” and in good health.

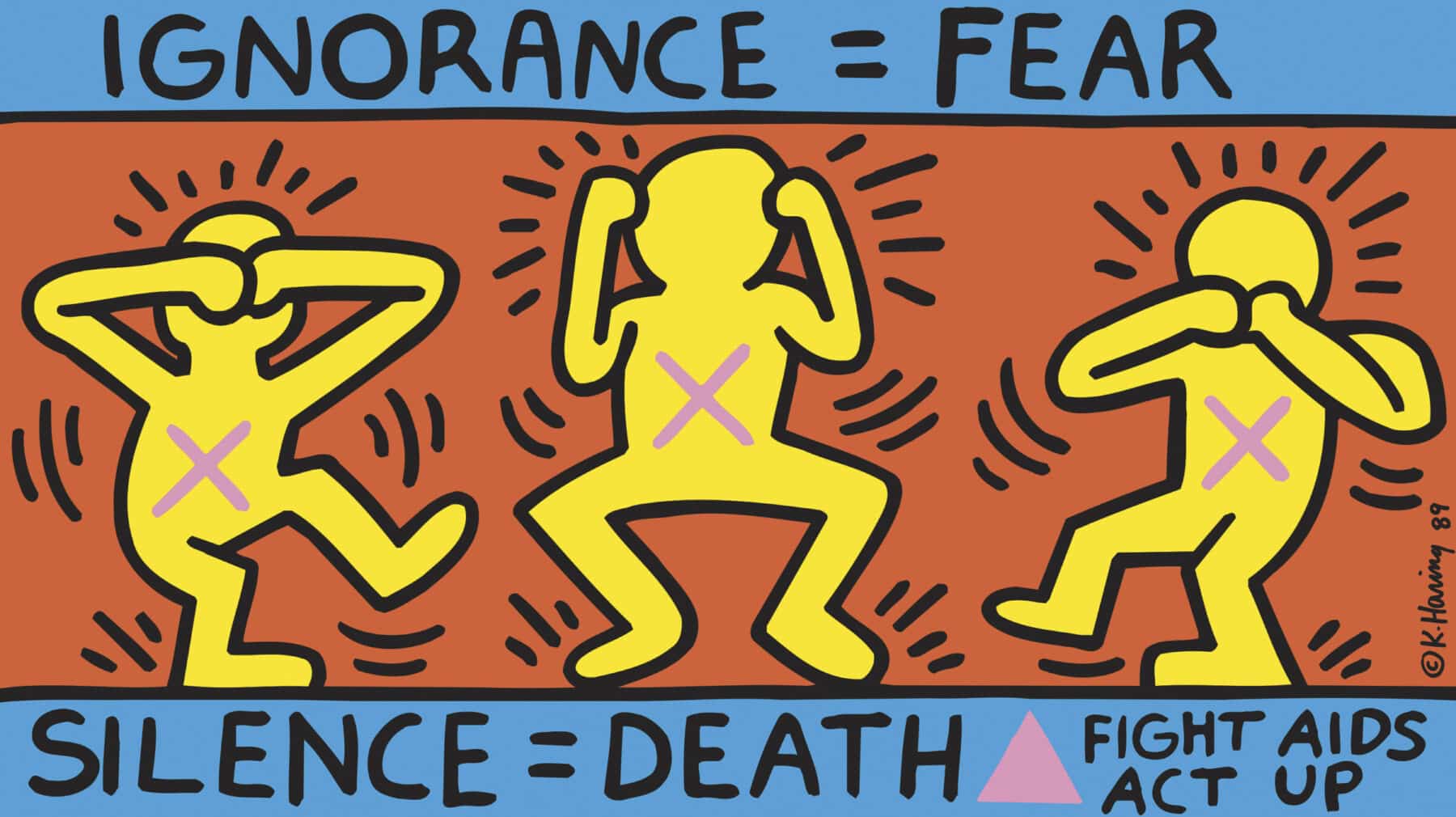

In late November 1989, Keith Haring came to ArtCenter to paint a mural for “A Day Without Art.” He spoke about running out of time and said he purposely chose art schools as the locations for his last works. The mural was commemorated on December 1, the second annual World AIDS Day. He told the Los Angeles Times, “My life is my art, it’s intertwined. When AIDS became a reality in terms of my life, it started becoming a subject in my paintings. The more it affected my life the more it affected my work.”

After my diagnosis, I went to the Manhattan Center for Living, a safe gathering place for people diagnosed with HIV. I met Tina Chow there, the first HIV-positive woman I had met who was also Asian and straight. She happened to be Antonio Lopez’s muse and she was also friends with Keith Haring. In her own right she was a model, jewelry designer, and style icon. At the end of Antonio’s life, Tina took care of him.

Another person I crossed paths in the early days was Juan Suárez Botas, a freelance illustrator and designer from Spain, who was my coworker at graphic designer Milton Glaser’s design firm. In this tight web, Tina, Juan, and I were patients of Dr. Paul Bellman, an internist who cared for thousands of HIV-positive people from 1986 onward. But after losing Tina and Juan, I could not shake the thought that if Dr. Bellman could not save them, he definitely would not save me. When they passed away, I left immediately. It’s a hard thing to share because a lot of people loved Dr. Bellman.

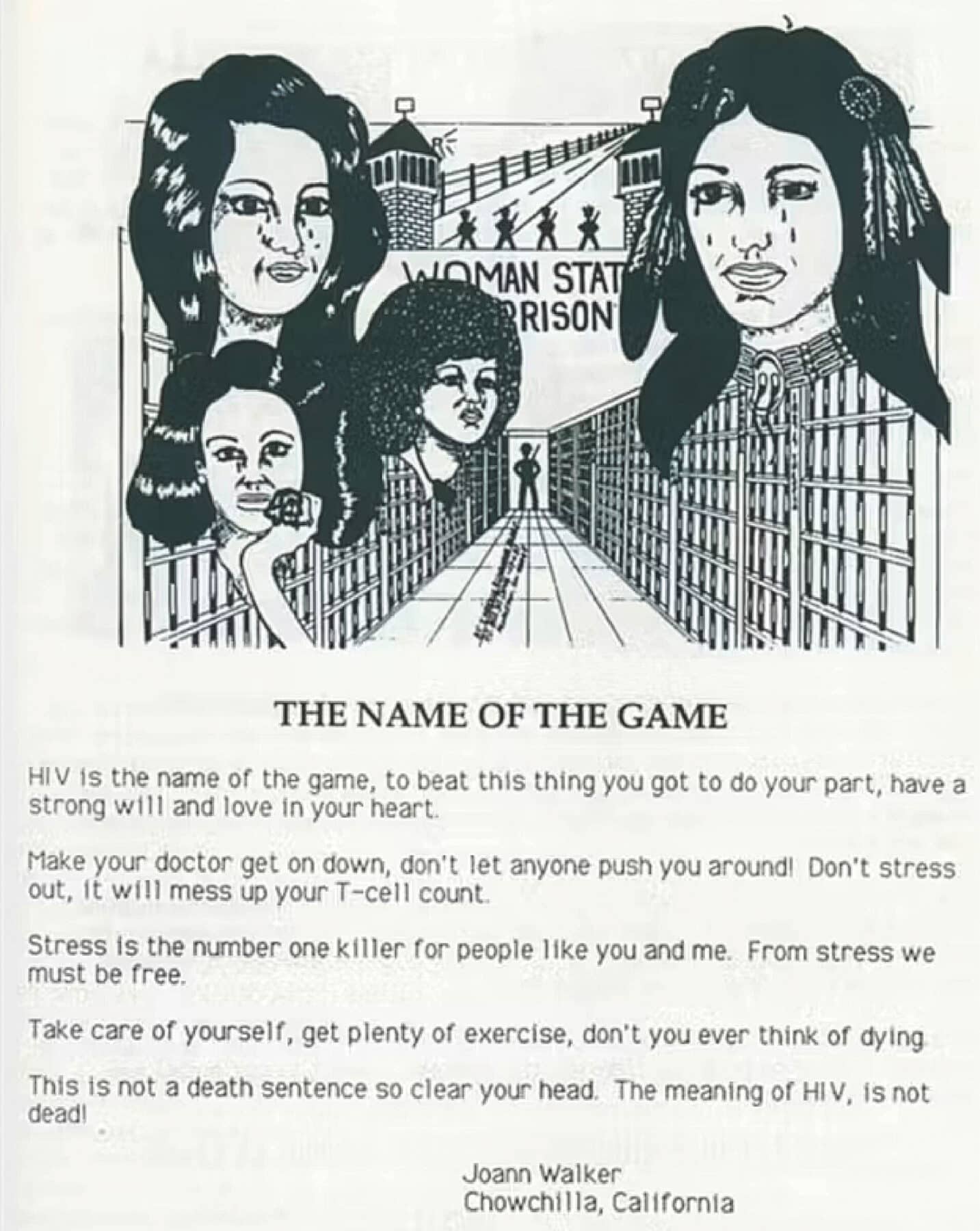

Together, many communities modeled a pathway for mutual care. In Chowchilla, California, the Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) was an exclusively female prison. Due to the absence of HIV/AIDS treatment and inadequate health care, women were dying from easily treatable health conditions.

Joann Walker, an advocate for the compassionate release of Betty Jo Ross, who was dying of AIDS at the CCWF, worked with the Coalition to Support Women Prisoners at Chowchilla. They collaborated with Judy Greenspan and other members of the ACT UP San Francisco’s Prison Issues Committee to hold prison officials accountable. The graphics they created to mobilize were self-distributed.