An expert on the social implications of technology responds to Shiv Ramdas’ “The Trolley Solution.”

Imagine a university without any teachers, just peer learners, open-access resources, and an office space full of high-speed internet-enabled computers, accessible to anyone between 18–30 years of age, regardless of any prior learning. That university is called 42. It does not have any academic instructors; the teachers are the self-starting students who have their eyes set on a job in Big Tech. Aided only by a problem-based learning curriculum, students gain a certificate of completion about three to five years after starting out. They are guaranteed internships in some of the world’s most prestigious firms and have set their sights on launching their careers as coders. 42’s philosophy is steeped in peer-to-peer learning, where human learners themselves spearhead the learning process.

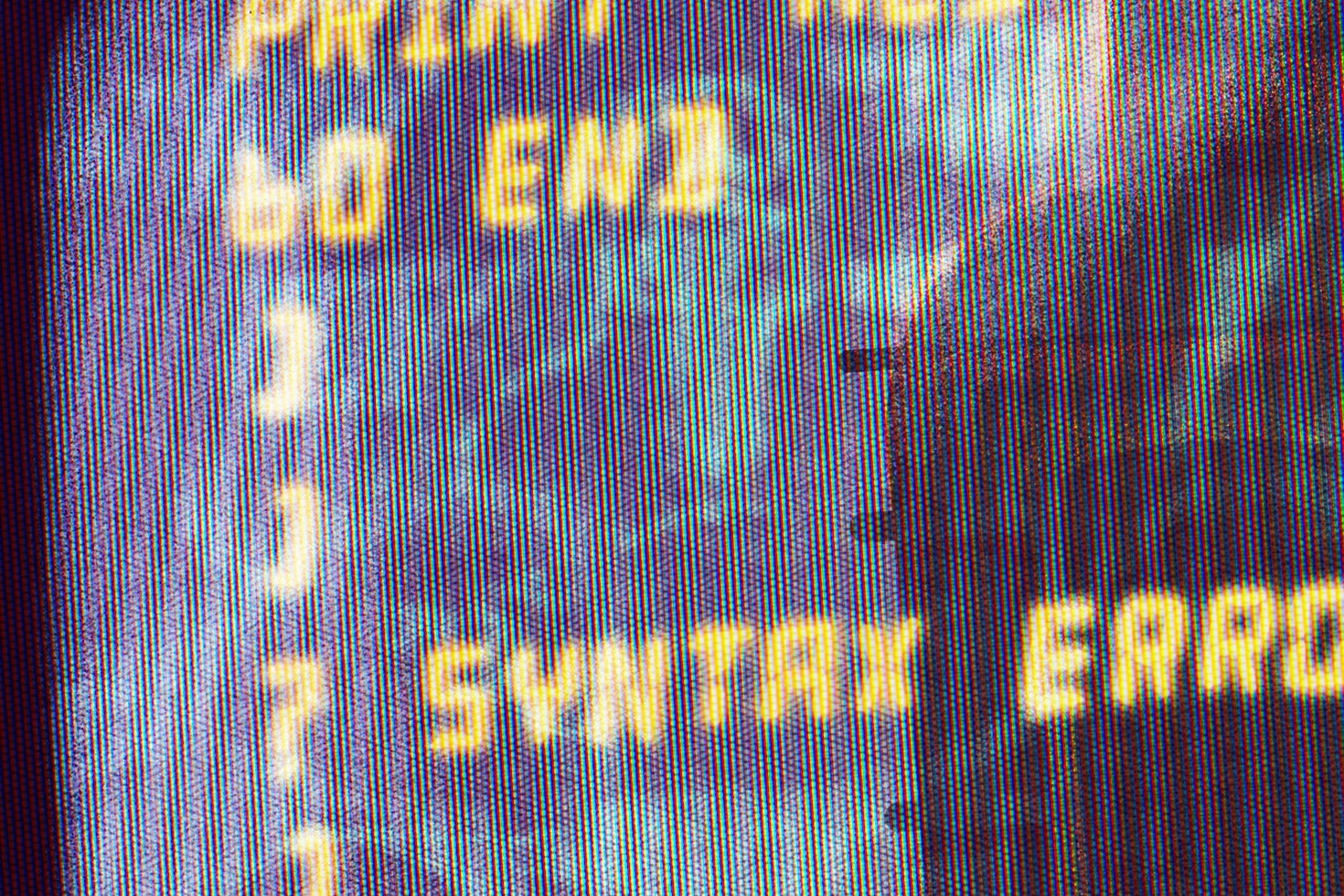

But could you conceive of an academic institution where A.I. would replace human teachers? Where you would not have to congregate in a physical building, but your teacher was an A.I. software system you could log onto from anywhere? Kind of like a mix between Khan Academy and a souped-up Alexa? The idea is not new. B. F. Skinner is often credited as the inventor of the “teaching machine.” According to Skinner, human learning could be done by teaching machines deliberately built to behaviorally engineer. Applying this approach, the student would reach a level of competency with the least number of errors through programmed instruction in increments. The teaching machine in its most ideal form would also allow for freedom of responses to questions posed. In his 1961 paper titled “Teaching Machines” in Scientific American, Skinner wrote, “Machines … could be programmed to teach, in whole and in part, all the subjects taught in elementary and high school and many taught in college.” But to think like Skinner is to negate your freedom and to relinquish your dignity at the hands of an authoritarian controlling machine. Learning happens biologically, freely, from within the inner person, and is the conclusion of a series of cognitive processes together with the lived experience that is unique to each human. Anything else would have potentially dire social and metaphysical implications.

In Shiv Ramdas’ “The Trolley Solution,” we are thrust into a university setting where the administration is considering new operational efficiencies, leading a human creative writing professor (Ahmed) and an A.I. (Ali) to battle in a head-to-head, semesterlong teach-off. The winner will be determined by surveillance techniques and outcome-based metrics. If Ahmed loses the duel, he and his colleagues will lose their academic careers and the students will be left with an A.I. software as their sole instructor.

Ahmed underestimates Ali, until he gets to know it more. He concedes a number of little minidefeats throughout the competition, though he believes they are mere “technicalities” to begin with. But over time, Ahmed begins to question his own decisions and motivations. In a last-ditch effort, he devises a plot to reveal Ali’s shortcomings, knowing that A.I.s don’t deal well with context, conflict, and consequences. In the end, Ahmed is declared the winner, but before celebrating his tenure, he reaffirms the value of Ali’s teaching. At the final board meeting, Ahmed learns that the head of school, Niyati, has lost her job. He is then greeted by Uma—the administrator who has been calling the shots all along and is revealed to be an automated management system.

The story reflects the real financial pressures that university administrators in the U.S., the U.K., Canada, and Australia are facing thanks to a steep decline in the number of international students, given COVID-19 border closures and concerns. Many staff and faculty members have had to agree to reduced pay; others have lost their jobs entirely. In Australia, more than 17,000 university jobs were lost in 2020 alone, a total of 13 percent of Australia’s pre-COVID university workforce. That number is set to keep rising through 2021.

Even absent the pandemic, universities have long faced the threat of fewer students for many reasons, including falling birth rates. Many have resorted to bespoke programs and introduced techno-centric pilots in the hope that some jobs might be saved through innovation. Under the direction mainly of financial executives charged with how to respond to acute reductions in profits, many universities have considered models that would allow for the rapid creation of courses, which could be sold online to students seeking remote learning asynchronous options without the need for too much human intervention beyond the course creation. We might call it the Uberization of education, because it’s a nascent stage of human-robot teaming. The process is as follows: Lecturer creates content in modular chunks; it is stored in the learning management platform of choice; it can be accessed at any time; assessment items are changeable to local markets; and assignments are graded automatically using advanced marking and feedback A.I.-based software. And no suggestions are off-limits; a dead professor’s online lectures were recently harvested, repackaged and re-used retrospectively without remuneration. In a way, this is a lot like what we see in “The Trolley Solution,” as Ahmed seems to realize that from a feasibility standpoint (operational, technical, economic), the ideal—both in terms of student learning and reducing administrative overhead—might be humans working with machines.

What you have then is a relatively “cheap” digital end-to-end product. Some universities have gone so far as claiming that this is the way of the future—that students actually prefer that kind of instruction. Perhaps it’s just because they don’t know better. Or perhaps they enjoy it but don’t realize the result is a substandard education. Or maybe administrators are simply ignoring the fact that students realize shoestring budget education is, in the word of one person I spoke to, “pathetic.”

In “The Trolley Solution,” Ahmed was set up for failure—by a machine, Uma. Eventually, he even viewed himself as falling short compared with the A.I. We humans, with all our frailties, all our vulnerabilities, and all our complex brain and bodily processes will somehow always believe that the machine has greater capacity to keep going. It doesn’t need to sleep; it doesn’t thirst; it can never find itself believing it is rejected or unloved. But just as we can never beat a machine at what it does best, machines cannot beat us at humanity. At worst a machine is a deepfake; at best, it is an imitation.

Ahmed is duped into believing the matchup is equal because of the way the question is posed to begin with: him versus it. Ahmed should have been asked how he could develop his teaching practice to incorporate it where “it” made sense pedagogically. Education can’t be Gigafied. It requires humanistic values like care, and it needs to be nurtured and developed and imbued and imparted and incorporated willingly by the learner. The truth is that an A.I., even one that passes the Turing test, cannot pass the blood test, or the heartbeat test, or the brain wave test, or the DNA test. Machines can’t succeed in the trolley problem because they do not know what it means to die, even if they do undergo planned obsolescence.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.