Airline deregulation

I agree with John R. Meyer and Thomas R. Menzies that the benefits of deregulation have been substantial (“Airline Deregulation: Time to Complete the Job” (Issues, Winter 2000). I also agree that some government policies need to be changed to promote competition.

I strongly opposed the 1985 decision to allow the carriers holding slots at the four high-density airports to sell those slots. Our experience has been that incumbent airlines have often refused to sell slots at reasonable prices to potential competitors. I am pleased that both the House and Senate Federal Aviation Administration reauthorization bills, now pending in conference committee, seek to eliminate slots at three of the four slot-controlled airports. According to a 1995 Department of Transportation (DOT) study, eliminating these slots will produce a net benefit to consumers of over $700 million annually from fare reductions and improved service.

Certain airport practices, such as the long-term leasing of gates, also limit opportunities for new entrants. This problem can correct itself over time if airports make more gates available to new entrants as long-term leases expire.

However, I disagree with the authors’ suggestion that we should adopt methods such as congestion-based landing fees to improve airport capacity. Higher fees would discourage smaller planes from taking off or landing during peak hours. In reality, there are few small private planes using large airports at peak hours, so this solution would not significantly reduce delays.

Nor would it be sound policy to discourage small commuter aircraft from operating at peak hours. This could disrupt the hub-and-spoke system, which has benefited many passengers under deregulation. Higher fees could prompt carriers to terminate service to communities served by smaller aircraft.

It is important for the government to protect low-fare carriers from unfair competition because they have been major providers of deregulation benefits to the traveling public. A 1996 DOT study estimated that low-fare carriers have saved passengers $6.3 billion annually.

Unlike the authors, I believe that it is important for DOT to establish guidelines on predatory pricing. DOT investigations and congressional hearings have uncovered a number of cases of predatory airline practices. These include incumbent airlines reducing fares and increasing capacity to drive a new competitor out of the market, then recouping their lost revenue by later raising fares.

The Justice Department’s investigation of alleged anticompetitive practices by American Airlines sends a strong message that major established carriers cannot resort to anticompetitive tactics. However, as I explained in a speech in the House of Representatives (Congressional Record, October 2, 1998, page H9340), DOT has broader authority to proceed against such practices and should exercise this authority, taking care not to inhibit legitimate fare reductions that benefit consumers.

The major airlines’ response has been to scream “re-regulation” at every opportunity when solutions are proposed. It is time that government and industry work constructively to find real solutions that expand the benefits of deregulation and “complete the job.”

REP. JAMES L. OBERSTAR

Democrat of Minnesota

The author is ranking Democratic member of the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

The article by John R. Meyer and Thomas R. Menzies reflects a recent Transportation Research Board report, Entry and Competition in the U.S. Airline Industry. The principal conclusion of the study is that airline deregulation has been largely beneficial and most markets are competitive. I strongly agree. Meyer and Menzies also correctly observe that airline deregulation has been accompanied by a paradox: However successful it can be shown to have been in the aggregate, there are enough people sufficiently exercised about one aspect or another of the deregulated industry to have created a growing cottage industry of critics and would-be tinkerers bent on “improving” it.

These tinkerers say they do not want reregulation. But I agree with Meyer and Menzies’ assertion that this tinkering is very unlikely to improve things. Only rarely do we get to choose between imperfect markets and perfect regulation or vice versa. That’s easy. The overwhelmingly common choice is between imperfect markets and flawed regulation administered by all-too-human regulators. And the overwhelming evidence is that when a policy has done as much good as airline deregulation, tweaking it to make it perfect is likely to create other distortions that will require other regulatory responses, and so on back toward where we came from.

I think it might further this important public policy debate to better understand the sources of two of the most important complaints about the deregulated airline system: its deteriorated levels of amenity and its highly segmented pricing system.

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) did not ever have the statutory power to regulate conditions of service for mainline air transportation. But it did engage in practices that encouraged service competition. It kept fares uniform and high at levels that allowed more efficient carriers enough margins to offer extra amenities to attract passengers. This forced less-efficient carriers to match in order to keep customers. This encouraged ever-better passenger service at prices more and more divorced from those necessary to support bare-bones service. This effect became particularly sharp when CAB forced jet operators to charge more than piston operators even though the jets had lower unit costs than the piston-engined aircraft they replaced. The result was a race to provide more and more space and fancier and fancier meals to passengers. This was the famous pre-deregulation era of piano bars and mai-tais.

In this mode, air travel wasn’t accessible to the masses, but it defined a level of amenity that was beyond what most consumers would choose to pay for. When deregulation allowed lower prices and new lower-amenity service alternatives, traffic burgeoned. As airlines struggled to reduce costs to match the fares that competition forced them to charge, they stripped out many of the service amenities passengers had become used to. Airline managements used to high service levels tried to offer higher levels of service at slightly higher prices, but consumers rejected virtually all of these efforts.

Coupled with this lower level of service were the highly differentiated fares that replaced the rigidly uniform fare structure of the regulated era. Competition meant that most passengers paid less than they had during the regulated era, but segmentation meant that some paid much more. These segmented fares were necessary to provide the network reach and frequency desired by business travelers. The expanded system generated more choices for business travelers and more bargain seats for leisure travelers.

Those paying high prices were accommodated in the same cabin with those flying on bargain fares, and they received the lower standard of service that most passengers were paying for. Airlines tried to accommodate the most lucrative of their business customers with the possibility of upgrades to first class and a higher level of amenity, but they could not do so for all payers of high fares.

So we have seen a potent political brew: 1) Higher-paying passengers sit next to bargain customers and get and resent a lower level of service than they received before deregulation. 2) Bargain customers remember the “good old days” (and forget that they couldn’t afford to fly very often) and are unhappy with the standard of service they are receiving but are unwilling to pay more. 3) Business passengers and residents of markets supported by the higher fares (frequent service to smaller cities) appreciate the frequency but resent the fare. In my view, the contrast between new service and old and between segmented fare structures and the old uniform fare structures has been a potent factor in feeding resentment among customers who take the network for granted but hate the selectively high fares that support it as well as the service that the average fare will support.

Menzies and Meyer are right: It would certainly help improve things to “complete the job” by ending artificial constraints on infrastructure use and adopting economically sound ways of rationing access where infrastructure is scarce. But I am afraid that the clamor to do something about airlines won’t die down until passengers recognize the price/quality distortions created by the previous regulatory regime and somehow erase the memory of a “fair” but artificially uniform pricing system that priced many of them out of the market, suppressed customer choice, and inhibited network growth.

MICHAEL E. LEVINE

Harvard Law School

Cambridge, Massachusetts

I agree with John R. Meyer and Thomas R. Menzies that it is time to complete the job started more than 20 years ago by the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978. But it is one thing to advocate that remaining government interventions such as slot controls, perimeter rules, and de facto prohibitions on market pricing be done away with. It is quite another thing to figure out ways of bringing about these results. I suggest that we have some evidence from other countries that changing the underlying institutions can be an effective way of bringing about further marketization.

About 16 countries have corporatized their air traffic control systems during the past 15 years, shifting from tax support to direct user charges. Although most of these charging systems are a long way from the kind of marginal-cost or Ramsey-pricing systems that economists would like to see, they at least link service delivery to payment and create a meaningful customer-provider relationship that was generally lacking before the change. And these reforms have already led to increased productivity, faster modernization, and reduced air service delays.

In addition, more than 100 large and medium-sized airports have been privatized in other countries during the same 15-year period. In most cases, privatized airports retain control of their gates, allocating them on a real-time basis to individual airlines. This is in marked contrast to practices at the typical U.S. airport, where most of the gates at most airports are tied up under long-term, exclusive-use lease arrangements by individual airlines. Hence, the privatized airports offer greater access to new airlines than do their typical U.S. counterparts.

Currently, the prospects for corporatizing the U.S. air traffic control system appear fairly good. The record level of airline delays in 1999 has led a growing number of airline chief executive officers to call for corporatizing or privatizing the system, and draft bills are in the works in Congress. A modest Airport Privatization Pilot Program would permit up to five U.S. airports to be sold or leased by granting waivers from federal regulations that would otherwise make such privatization impossible. Four of the five places in that program have now been filled–but all by small airports, not by any of the larger airports where access problems exist. An expanded program is clearly needed.

Incentives matter. That is why we want to see greater reliance on pricing in transportation. But institutional structures help to shape incentives. Airports and air traffic control will have stronger incentives to meet their customers’ needs (and to use pricing to do so) when they are set up as businesses, rather than as tax-funded government departments.

ROBERT W. POOLE, JR.

Director of Transportation Studies

Reason Public Policy Institute

Los Angeles, California

Plutonium politics

“Confronting the Paradox in Plutonium Policies” (Issues, Winter 2000) by Luther J. Carter and Thomas H. Pigford contains a number of interesting ideas and proposals, some of which may merit consideration. However, others are quite unrealistic. For example, the successful establishment of international and regional storage facilities for spent nuclear fuel could offer fuel cycle and nonproliferation advantages in some cases. However, the suggestion by the authors that the French, British, and presumably others should immediately stop all of their reprocessing activities is likely to be strongly resisted and, if pursued aggressively by the United States, could prove very damaging to our nonproliferation interests. In addition, it is neither fair nor accurate to say, as the authors have, that the international nonproliferation regime will be incomplete unless and until all spent fuel is aggregated in a limited number of international or regional storage facilities or repositories. These suggestions and assertions, in my view, are too sweeping and grandiose, and they overlook the complexity of the international nuclear situation as it exists today.

I certainly agree with the authors that it is important for the international community to come to better grips with the sizeable stocks of excess separated plutonium that have been built up in the civil fuel cycle and to try to establish a better balance in the supply and demands for this material. We also face major challenges in how best to dispose of the vast stocks of excess weapon materials, including highly enriched uranium and plutonium, now coming out of the Russian and U.S. nuclear arsenals. It also would improve the prospects for collaborative international action on plutonium management if there were a far better understanding and agreement between the United States and the Western Europeans, Russians, and Japanese as to the role plutonium should play in the nuclear fuel cycle over the long term.

However, it must be recognized that there remain some sharply different views between the United States and other countries over how this balance in plutonium supply and demand can best be achieved and over the role plutonium can best play in the future of nuclear power. Many individuals in France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and even in the United States (including many people who are as firmly committed to nonproliferation objectives as are the authors) strongly believe that over the long term, plutonium can be an important energy asset and that it is better either now or later to consume this material in reactors than to indefinitely store it in some form, let alone treat it as waste.

I believe that it is in the best interest of the United States to continue to approach these issues in a nondoctrinal manner that recognizes that we may need to cope with a variety of national situations and to work cooperatively with nations who may differ with us on the management of the nuclear fuel cycle. In some cases, the best solution may be for the United States to continue to encourage the application of extremely rigorous and effective safeguards and physical security measures to the recycling activities that already exist. In other cases, we might wish to encourage countries who strongly favor recycling to ultimately wean themselves off of or avoid the conventional PUREX reprocessing scheme that produces pure separated plutonium and to consider replacing this system with potentially more proliferation-resistant approaches that allow some recycling to occur, while always avoiding the presence of separated plutonium. However, to be credible in pursuing such an option, which still needs to be proven, the United States will have to significantly increase its own domestic R&D efforts to develop more proliferation-resistant fuel cycle approaches. In still other cases, it might prove desirable to try to promote the establishment of regional spent fuel storage facilities.

National approaches to the nuclear fuel cycle are likely to continue to differ, and what the United States may find tolerable from a national security perspective in one foreign situation may not apply to other countries. We should avoid deluding ourselves into believing that there is one technical or institutional approach that will serve as the magic solution in all cases.

HAROLD D. BENGELSDORF

Bengelsdorf, McGoldrick and Associates

Bethesda, Maryland

The author is a former senior official at the U.S. Departments of State and Energy.

Time will tell whether Luther J. Carter and Thomas H. Pigford’s vision for reducing plutonium inventories by ending commercial reprocessing and disposing of used nuclear fuel by developing a network of waste repositories will become reality.

Without question, this vision embodies over-the-horizon thinking. Nonetheless, Carter and Pigford are solidly real-world in their belief that the United States must build a repository without delay to help ensure nuclear energy’s future and to dispose of surplus weapons plutonium in mixed oxide (MOx) reactor fuel.

The United States does not reprocess commercial spent fuel, but France, Great Britain, and Japan have made the policy decision to use this technology. As the global leader in nuclear technology, however, we can also lead the world in a disposal solution. Moreover, we who have enjoyed the benefits of nuclear energy have a responsibility to ensure that fuel management policy is not simply left to future generations.

So why are we at least 12 years behind schedule in building a repository? The answer is a lack of national leadership. Extensive scientific studies of the proposed repository at Yucca Mountain, Nevada, are positive, and the site is promising. But, as Carter and Pigford correctly note, it is “a common and politically convenient attitude on the part of…government…to delay the siting and building of [a] repository.”

Delay and political convenience are no longer acceptable. Nuclear energy is needed more than ever to help power our increasingly electrified, computerized economy and to protect our air quality. In addition, Russia has agreed to dispose of surplus weapons plutonium only if the United States undertakes a similar effort. Without timely construction of a repository, these important goals will be difficult to realize.

Leadership from the highest levels of government is needed to ensure the following conditions for building a repository that is based on sound science and has a clear, firm schedule:

- Involvement by the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (the preeminent national authority on radiation safety) in setting a radiation standard for Yucca Mountain that protects the public and the environment. 2) Moving used fuel safely and securely to the repository when construction begins. 3) Prohibiting the government from using repository funds to pay legal settlements arising from its failure to move fuel from nuclear power plants.

Likewise, governmental leadership is vital to move the U.S. MOx program forward. Congress and the administration must provide funding for the infrastructure for manufacturing MOx fuel; a continued commitment to the principles and timetables established for the program; and leadership in securing international support for Russia’s disposition effort.

It has been said that future is not a gift, but an achievement. A future with a cleaner environment and greater security of nuclear weapons materials will not be a gift to the United States, but we can achieve this future by using nuclear energy. Governmental leadership is the key to ending the delays that have held up timely development of a repository for the byproducts of this important technology.

JOE F. COLVIN

President and Chief Executive Officer

Nuclear Energy Institute

Washington, D.C.

www.nei.org

In Luther J. Carter’s and Thomas H. Pigford’s excellent and wise article, I find the following points to be of critical importance: (1) that the U.S. and Russia expedite their disposition of separated weapons-grade plutonium; (2) that all the countries with advanced nuclear power programs move to establish a global system for spent fuel storage and disposal; and (3) that the nuclear industries in France, Britain, and Russia halt all civil fuel reprocessing.

Of these, the third point is certainly the most controversial and will require the most wrenching change in policy by significant parts of the nuclear industry in Europe and elsewhere. But the authors’ central argument is, in my view, compelling: that the separation, storage, and recycling of civil plutonium pose unnecessary risks of diversion to weapons purposes. These risks are unnecessary because the reprocessing of spent fuel offers no real benefits for waste disposal, nor has the recycling of plutonium in MOx fuel in light water reactors any real economic merit. To this reason, I would add one other: An end to civilian reprocessing would markedly simplify the articulation and verification of a treaty banning the production of fissile material for weaponsan often-stated objective of disarmament negotiations over the past several years. With civil reprocessing ongoing, such a treaty would ban any unsafeguarded production of plutonium (and highly enriched uranium) but, of necessity, allow safeguarded production, vastly complicating verification arrangements.

I am more ambivalent about the authors’ prescription to give priority to disposition of the separated civil plutonium, especially if this is done through the MOx route. Such a MOx program would put the transport and use of separated civil plutonium into widespread commercial or commercial-like operation. At the end of the disposition program, the plutonium would certainly be in a safer configuration (that is, in spent fuel) than at present. But while the program is in progress, the risks of diversion might be heightened, particularly compared to continued storage at Sellafield and La Hague, where the plutonium (I imagine) is under strong security. This may not be true of the civil plutonium in Russia, however, and there a program of disposition looks more urgent and attractive. Also, to tie up most reactors in the burning of the civil plutonium could substantially slow the use of reactors to burn weapons plutonium, a more important task.

Immobilization, the alternative route of disposition of civil plutonium that the authors discuss, would not have these drawbacks, at least to the same degree. One reason why the MOx option has received the most attention in the disposition of weapons plutonium is that the Russians have generally objected to immobilization, partly on the grounds that immobilization would not convert weapons-grade plutonium to reactor-grade as would be done by burning the plutonium in a reactor. This criticism, at least, would be moot for the disposition of civil plutonium.

HAROLD A. FEIVESON

Senior Research Policy Analyst

Princeton University

Princeton, New Jersey

Although many aspects of “Confronting the Paradox in Plutonium Policies” deserve discussion, I limit my comments to the fundamental inaccurate premise that “A major threat of nuclear weapons proliferation is to be found in the plutonium from reprocessed nuclear fuel.” Just because something is stated emphatically and frequently does not make it valid. First, let’s recall why there is a substantial difference (not “paradox”) in plutonium policies. Some responsible countries that do not have the U.S. luxury of abundant inexpensive energy made a reasoned choice to maximize their use of energy sources–in this case, by recycling nuclear fuel. The recycling choice is based on energy security, preservation of natural resources, and sustainable energy development. When plutonium is used productively in fuel, one gram yields the energy equivalent of one ton of oil! Use it or waste it? Some countries, such as France and Japan, have chosen to use it. MOX fuel has been used routinely, safely, and reliably in Europe for more than 20 years and is currently loaded in 33 reactors.

In recycling, separation of reactor-grade plutonium is only an intermediate step in a process whose objective is to use and consume plutonium. Recycling therefore offers a distinct nonproliferation advantage: The plutonium necessarily generated by production of electricity in nuclear power plants is burned in those same plants, thereby restricting the growth of the world’s inventories contained in spent fuel.

As the authors recognize, recycling minimizes the amount of plutonium in the waste. It also results in segregation and conditioning of wastes to permit optimization of disposal methods. As one of the authors previously wrote, one purpose of reprocessing is “to convert the radioactive constituents of spent fuel into forms suitable for safe, long-term storage.” Precisely!

The authors take for granted that civil plutonium is the right stuff to readily make nuclear weapons, without mentioning how difficult it would be. There are apparently much easier ways to make a weapon than by trying to fashion one from civil plutonium (an overwhelming task) diverted from responsible, safeguarded facilities (another overwhelming task). One might ask why a terrorist or rogue state would take an extremely difficult path when easier paths exist. Those truly concerned about nonproliferation need to focus resources on real, immediate issues such as “loose nukes”: weapons-grade materials stockpiled in potentially unstable areas of the world.

Although the authors state that safeguards “reduce the risk of plutonium diversions, thefts, and forcible seizures to a low probability,” one concludes from the thrust of the article that the authors consider national and international safeguards and physical protection measures to be, a priori, insufficient or inefficient. The impeccable record belies this idea.

The authors speak of the need for action by “the peace groups, policy research groups, and international bodies that together make up the nuclear nonproliferation community.” However, these entities participate in the nonproliferation community, but they do not constitute it. Industry is a lynchpin of the nonproliferation community. We not only believe deeply in nonproliferation, but the very existence of the industry depends on it. Those who prefer to criticize the industry should first reflect on that. Right now, industry is making substantial contributions to the international efforts to dispose of excess weapons-grade plutonium. Without the industrial advances made in recycling, neither MOx nor immobilization could be effective.

Open dialogue is irreplaceable for nonproliferation, as well as for optimization of the nuclear industry’s contribution to global well-being. A Decisionmakers’ Forum on a New Paradigm for Nuclear Energy sponsored by Sen. Pete Domenici and the Senate Nuclear Issues Caucus recognized the importance of not taking action that would preclude the possibility of future recycling. (This does not challenge current U.S. policy or programs but would maintain for the future an option that might become vital.) The forum included representatives of the political, nonproliferation, and academic communities, as well as national labs and industry.

I sincerely hope that we, as Americans, can progress from preaching to dialogue and from “Confronting the Paradox in Plutonium Policies” to “Recognizing the Validity of Different Energy Choices.” Let’s solve real problems, rather than building windmills to attack.

MICHAEL MCMURPHY

President and Chief Executive Officer

COGEMA-U.S.A.

Washington, D.C.

Luther J. Carter and Thomas H. Pigford’s view is tremendously thought provoking. The idea of creating a global network of storage and disposal centers for spent nuclear fuel and high-level radioactive waste is certainly worthwhile for providing a more healthy and comfortable world nuclear future. In particular, their proposal that the United States should establish a geologic repository at home that would be the first international storage center seems extremely attractive for potential customers.

Spent fuels in a great number of countries, including Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, originated in the United States, and under U.S. law they cannot be transferred to a third-party state without prior U.S. consent. The easiest way to gain U.S. approval is for the United States to become a host country. There might be several standards and criteria for hosting the center. The host organization involved would have to have the requisite technical, administrative, and regulatory infrastructure to safely accommodate the protracted management of spent fuel. To be politically acceptable, the host nation will have to possess solid nonproliferation credentials and be perceived as a stable and credible long-term custodian. The United States undoubtedly satisfies these conditions.

The challenges associated with establishing an international center are somewhat different, depending on whether it is aimed at final disposal or interim storage. To be viable, a final repository will have to be in a suitable technically acceptable geologic location, and the host will have to be prepared to accept spent fuel from other countries on a permanent basis. A proposal by a state to receive and store spent fuel from other states on an interim basis entails less of a permanent obligation but leaves for later determination and negotiation what happens to the spent fuel at the end of the defined storage time.

The international network proposed by Carter and Pigford is obviously based on the final disposal concept. In view of the risk of taking an extremely long time to fix the location of a final repository that is both technically and socially acceptable, however, the concept of interim storage looks more favorable for moving the international solution forward. It might be more preferable from the viewpoint of customer nations as well, because to keep options open, some customers do not want to make an impetuous choice between reprocessing or direct disposal but to store their own spent fuel as a strategic material under appropriate international safeguards. The most difficult obstacle would be gaining world public support. Without a clear-cut statement about why the network is necessary, people would not willingly support the idea. My view is that the network must be directly devoted to an objective of worldwide peace–that is, the further promotion of nuclear disarmament as well as nuclear nonproliferation. If the network is closely interrelated to an international collaborative program for further stimulation of denuclearization, then it might have much broader support from people worldwide.

ATSUYUKI SUZUKI

University of Tokyo

Tokyo, Japan

Higher education

As we try to think carefully about the extravagantly imagined future of cyberspace, it is helpful to sound a note of caution amid the symphony of revolutionary expectations [like those expressed in Jorge Klor de Alva’s “Remaking the Academy in the Age of Information” (Issues, Winter 2000)]. For over a century, many thoughtful observers have suggested that the ever-advancing scientific and technological frontier either had or inevitably would transform our world, its institutions, and our worldview in some extraordinary respects. In retrospect, however, despite the substantial transformation of certain aspects of society, actual events have both fallen somewhat short of what many futurists had predicted (for example, we still have nation-states and rather traditional universities) and often moved in unanticipated directions. In particular, futurists once again underestimated the strength and resilience of existing belief systems and the capacity of existing institutions to transform themselves in a manner that supported their continued relevance and, therefore, existence.

Nevertheless, institutions such as universities that deal at a very basic level with the creation and transmission of information will certainly experience the impact of the new information age and its associated technologies in a special way. Even if we assume the continued existence of universities where students and scholars engage in face-to-face conversation or work side by side in its libraries and laboratories, there is no question that new communications and computation technologies will lead to important changes in how we teach and learn, how we conduct research, and how we interact with each other and the outside world. Nevertheless, I believe that these developments are unlikely to undermine the continued social relevance of universities as we understand them today.

Despite the glamour, excitement, and opportunities provided by the new technologies, I believe that the evidence accumulated to date regarding how students learn indicates that the particular technologies employed do not make the crucial difference. If the quality of the people (and their interaction), the resources, and the overall effort are the same, one method of delivery can be substituted for another with little impact on learning, providing, of course, that those designing particular courses are aware of how people learn. The principal inputs in the current model are faculty lectures or seminars, textbooks, laboratories, and discussions among students and between students and faculty. In other words, students pursuing degrees learn from each other, from faculty, from books and from practice (laboratories, research papers, etc.). It is my belief that the exact technologies used to bring these four inputs together are not the crucial issue for learning. What is important, however, is to remember that one way or another all these inputs are important to effective learning at the advanced level, particularly the interaction between learners and teachers.

Since ongoing feedback between faculty and students and among students themselves will always be part of quality higher education, it probably follows that to a first approximation the costs of producing and delivering the highest-quality programs are similar across the various technologies as long as all the key inputs identified above are included. I do not believe that one can put a degree-based course on the Web and simply start collecting fees without continuing and ongoing attention to the intellectual and other needs of the students enrolled.

A new world is coming, but not all of the old is disappearing.

HAROLD T. SHAPIRO

President

Princeton University

Princeton, New Jersey

Jorge Klor de Alva is the president of a for-profit university of nearly 100,000 students. I am a teacher at a college that has fewer than 1,000 students on its two campuses (Annapolis and Santa Fe) and is eminently not for profit. Yet, oddly enough, our schools have some things in common. We both have small discussion classes and both want to do right by our students. We both see the same failings in the traditional academy, chief of which is that professors tend to suit their own professional interests rather than the good of their students. But in most things we are poles apart, though not necessarily at odds.

Yet were we a hundred times as large as we are, we would not (I hope) take the doom-inducing dominating tone toward other schools that de Alva takes toward us. I think that more and better-regulated proprietary schools are a good and necessary thing for a country in urgent need of technically trained workers. But why must education vanish so that technical training may thrive? The country also needs educated citizens, and as human beings citizens need education, for there is a real difference between training and education.

I ardently hope that many of his students have been educated before they come to learn specialized skills at de Alva’s school. Training should be just as he describes it: efficient, focused on the students’ present wishes, available anywhere, and flexible.

Education, on the other hand, is inherently inefficient, time-consuming, dependent on living and learning together, and focused on what students need rather than on what they immediately want. That is why our students submit to an all-required curriculum. It is our duty as teachers to think carefully about the fundamentals a human being ought to know; it is their part not to have information poured into them but to participate in a slow-paced, prolonged shaping of their feelings and their intellect by means of well-chosen tools of learning. The aim of education is not economic viability but human viability. Without it, what profit will there be in prosperity?

Could de Alva be persuaded to become an advocate of liberal education in the interests of his own students? Our two missions, far from being incompatible, are complementary.

There is one issue, however, in respect to which “Remaking the Academy” seems to me really dangerous: in supporting the idea that universities and colleges should go into partnership with business. I know it is already going on, but it seems to me very bad–not for proprietary schools, for which it is quite proper, but for schools like ours. Businesses cannot help but skew the mission of an educational institution; why else would they cooperate? How then will one of the missions of the academy survive–the mission to reflect on ways of life that emphasize change over stability, information over wisdom, flexibility over principle? For trends can be ridden or they can be resisted, and somewhere there ought to be a place of independence where such great issues are freely thought about.

EVA BRANN

St. John’s College

Annapolis, Maryland

Universities have a long and distinguished history that has earned them widespread respect. But as Jorge Klor de Alva points out, the problem with success is that it creates undue faith in what has worked in the past. The University of Phoenix has been an important innovator in higher education, but the real trailblazing has been taking place within corporate education. Because corporations place a premium on efficiency and are free of the blinders of educational tradition, they have become leaders in the development of new approaches to education. At the VIS Corporation, which helps companies use information technology in their training programs, we have learned a number of preliminary lessons that should be helpful to all educators interested in using technology to improve effectiveness.

The process and time to deliver most educational content can be dramatically streamlined using technology. Computer-based delivery often makes it possible to condense a full day of classroom material into one or two hours without the need for any instructor. This is possible because computers essentially provide individual tutoring, but without the cost of an individual tutor for each student. Of course, computer-only instruction will not work for all types of material, but we need to recognize that because a given training course requires some personal interaction, say role-playing exercises, it does not mean that the entire course must be taught in a classroom with a live instructor.

Different types of content require different approaches. The traditional ways of disaggregating educational content by subject area are not helpful here, because within each subject area a variety of types of learning must take place. In trying to figure out a way to help us choose the right approach to education, we broke down learning into four broad categories that transcend subject area and developmental level: informational, conceptual, procedural, and behavioral learning.

Informational and conceptual learning are the types of content that are normally considered the traditional subject matter of education. Informational learning includes what we normally think of as information and data. This content, which changes rapidly and has many small pieces, is ideal for technology delivery and constitutes the vast majority of what is available on the Internet. Conceptual learning involves understanding models and patterns that allow us to use information effectively and modify our actions as situations change. This is a significant part of the learning delivered in higher education and by master teachers. With a computer, conceptual learning can be advanced through self-guided exploration of software models. Procedural and behavioral learning are the traditional province of corporate training. These are rarely taught in educational institutions but are critical to how effectively an individual can accomplish goals at work or in life. Interactive simulation is the best delivery mechanism for procedures, whereas behavioral learning needs a mix of video demonstration and live facilitation.

Effective technology-based learning requires that the content be focused on the learner’s needs and learning style, not on the instructor’s standard approach. In a classroom we sit and learn in the way that the teacher structures the materials. A good instructor will use a variety of techniques to reach the largest number of students, but the process is ultimately linear. Technology, on the other hand, offers the opportunity to deliver content in a wide range of forms that can be matched to the content needs and the learning style of each individual. A second factor is that different people have dramatically different learning styles and that no one methodology is a perfect solution for everyone. Technology delivery offers the option to deliver the content in the best way for each individual learner.

Although the process of designing content for performance-based learning that is common in corporate education is much more straightforward than for the general education provided in universities, the steps we have developed will be useful in preparing any course:

- Identify and categorize the knowledge and skills exhibited by superior performers.

- Develop an evaluation model (test, game, questionnaire, or 360-degree evaluation) that can determine exactly what each individual most needs to learn.

- Create the content delivery modules and a personalized navigation capability to let each individual get at the content that they need or want in the most flexible way.

- Develop a way to assess what the student has learned and to certify that achievement.

By following this process in numerous settings, it is likely that over the next decade we will learn how to use the “right” combinations of technology to make all types of education more efficient and more focused on the needs of each student, rather than on the needs of the teacher or the curriculum

ANDY SNIDER

Managing Director

VIS Corporation

Waltham, Massachusetts

Mending Medicare

My friend Marilyn Moon has done her usual exemplary job of puncturing some of the mythology surrounding Medicare “reform” in “Building on Medicare’s Strengths” (Issues, Winter 2000), but one of her arguments already needs updating, and I would like to take issue with another.

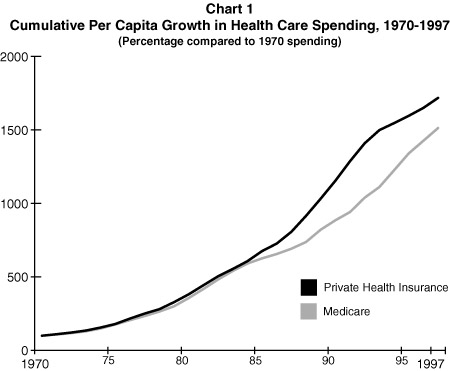

Moon does an appropriately thorough job of demolishing the falsehoods surrounding the relative cost containment experiences of Medicare and the private sector by demonstrating that, over time, Medicare has been more effective at cost containment; but the data she uses extend only through 1997, which turns out to have been the last year of a period of catch-up by private insurance, in which the gap between Medicare and private cost growth was significantly reduced. We now have data from 1998 and lots of anecdotal information from 1999 that show that, largely as a result of the provisions of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Medicare cost growth has essentially stopped, at least temporarily, while private sector-costs are accelerating. In other words, Moon’s assertions about the relative superiority of Medicare’s cost containment efforts are, if anything, understated.

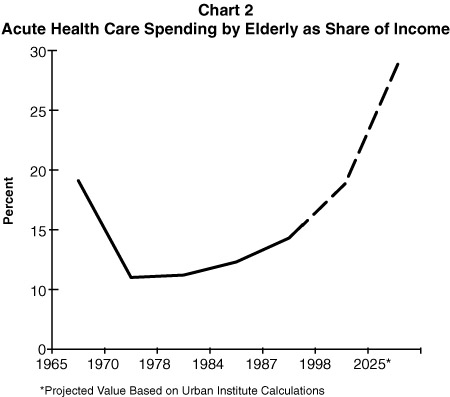

Moon does seem to accept the conventional wisdom that the growth in Medicare’s share of national income over the next few decades, arising from the combined effect of the aging of the baby boomers and the continued propensity of health care costs to grow more quickly than the economy as a whole, constitutes a significant problem that requires reform. She points out, for example, that under then-current projections, Medicare’s share of national income will grow from roughly 2.53 percent in 1998 to 4.43 percent in 2025 (although those numbers are likely to be modified downward in response to the more recent data described above). In doing so, I fear that like many of the rest of us she has fallen into a trap quite deliberately and systematically laid by forces that are opposed to the very concept of social insurance programs such as Medicare and Social Security, and especially to the intrinsically redistributive character of such programs.

Obviously, as a society ages, it will spend relatively more of its resources on health care and income support for older people, all other things being equal. It will also, presumably, spend relatively less of its resources on younger people. But spending 4.5 percent of gross domestic product on health care for the elderly is only a problem, let alone a crisis, if people are unwilling to do so. Perhaps more important, as the experience in public finance over the past five years should once again have reminded us, if the economy grows enough, we can double or triple or quadruple what we spend on health care for the elderly and everyone else in society will still have more real income left over.

Every other industrialized nation, except Australia, already has a higher proportion of old people in its population than does the United States, and all provide their elderly and disabled citizens with more generous publicly financed benefits than we do. None of those nations appears to be facing imminent financial disaster as a result. The “crisis” in financing Medicare and Social Security has largely been manufactured by individuals and institutions with a political agenda to shrink or abolish those programs, and we should stop letting ourselves fall victim to their propaganda.

BRUCE C. VLADECK

Director, Institute for Medicare Practice

Mount Sinai School of Medicine

New York, New York

Health care is complicated. When people have to make decisions on complicated issues, they typically limit the number of decision criteria they address and instead use a “rule of thumb” that encompasses just one criterion. That’s what federal decisionmakers have done with the Medicare program, and their single criterion has been cost. Often, the focus has been still more narrow, coming down to a matter of the prices paid to providers and managed care plans. As Marilyn Moon notes, Medicare (the biggest health care purchaser in the country), has been able to control the price it pays, within the limits of interest group politics, to keep federal cost increases in the program at levels at or below those found in the private sector. Indeed, many federal innovations in payment policy have been adopted by private insurers.

However, federal costs depend on more than federal prices; federal costs can go down while the overall health care costs of those covered by the program go up. And as Moon implies, many other criteria should be used to assess the program today and in the future. One such criterion that is of critical importance to people on Medicare is security. This is, after all, an insurance program. It was designed not only to pay for needed health services but to provide older Americans (and later people with serious disabilities) with the security inherent in knowing that they were “covered” whatever happened.

Many recent proposals to “reform” Medicare seem to reflect an unwillingness to deal with the multiple factors that affect the program’s short- and long-term costs. In particular, reforms that would have a defined “contribution” rather than a defined “benefit” seem to wrap a desire to limit the federal government’s financial “exposure” in the language of market efficiency and competition. In the process, such proposals ignore the importance of Medicare’s promise of security.

Health care markets are more feasible when competing units are relatively flexible entities such as health plans rather than more permanent structures such as hospitals. Thus, competition has become more apparent in the Medicare managed care market. Has this led to greater efficiency, even in terms of federal cost? Multiple analyses indicate that Medicare has paid higher prices than it should have to managed care plans, given the risk profile of the people they attract. Those with serious health problems are more risk averse and thus less likely to switch to a managed care plan even when they could reap significant financial advantages. The desire for security that comes with working with a known system and known and trusted health care providers is a powerful incentive for people on Medicare. It is part of the reason that nearly 15 years after risk-contract HMOs became available to people on Medicare, only 16 percent are enrolled in such plans. That proportion is likely to grow as people who are experienced with managed care (and have had a good experience) become eligible for Medicare. But there is a big difference between such gradual growth in HMO use and the proposed re-engineering of the program that would make it virtually impossible for millions of low- to moderate-income people to stay in the traditional Medicare program. The discontinuities in coverage and clinical care that are likely in a program where there is little financial predictability for either health plans and providers on the one hand, or members and patients on the other, may be just as costly in the long term as any gains attributable to “market efficiencies” that focus on price reductions in the short term. In short, echoing Moon’s arguments, we do not need to rush headlong into reform proposals based on the application of narrow decision heuristics. We need to face the challenge of considering multiple decision criteria if we are to shape a Medicare program that will do an even better job in the future of providing health and security to older Americans (and their families) as well as to people with disabilities in a manner that is affordable for us all.

SHOSHANNA SOFAER

School of Public Affairs

Baruch College

New York, New York

Jeffersonian science

Issues recently published (Fall 1999) two most commendable articles on the weaknesses of our definitions of research and how those definitions affect, and even inhibit, the most efficient funding of publicly supported science.

In “A Vision of Jeffersonian Science,” Gerald Holton and Gerhard Sonnert skillfully elaborated the flaws in our rigid descriptions of and divisions between basic and applied research. The result has been the perpetuation of the myth that basic and applied research are mutually exclusive. The authors bring us to a more realistic and flexible combination of the two with their term “Jeffersonian research.”

As the authors cited, the Jeffersonian view is compatible with the late Donald Stokes’ treatise Pasteur’s Quadrant. In it, we were reminded that Pasteur founded the field of microbiology in the process of addressing both public health and commercial concerns, the point being that solving problems is not mutually exclusive of discovering new knowledge. In fact, the two are often comfortably inseparable. Pasteur was not caught in a quagmire of definitions and divisions. He was asking questions and finding answers.

At a time when most fields and disciplines of science and engineering are spilling into each other and shedding light on each other’s unanswered questions, it is somewhat mysterious that we cling to the terms basic and applied research. We can hardly complain that members of Congress line up in one camp or another if we in the science community continue this bifurcation.

Lewis M. Branscomb’s article “The False Dichotomy: Scientific Creativity and Utility” gives us a fine history of the growth and evolution of publicly funded research in the United States, with all of its attendant arguments and machinations. Branscomb concludes, “An innovative society needs more research driven by societal need but performed under the conditions of imagination, flexibility, and competition that we associate with basic science.” No one can argue with that.

Both articles make reference to the late “dean of science” in Congress, George Brown, who for many years chided the science community on the obsolescence of our descriptions of research and on the need for science to address societal concerns and problems. These two articles suggest that we are on the path to doing so.

As our society continues to move beyond the constraints of Cold War policy and practice, the debate presented in these two articles brings us to a healthy discussion of defining the role and responsibility of science and engineering for a new economy and a new century. More flexible definitions and more open discussions of the research that reflect our actual work rather than our old lexicons are an important beginning.

RITA COLWELL

Director

National Science Foundation

Arlington, Virginia

Minority engineers

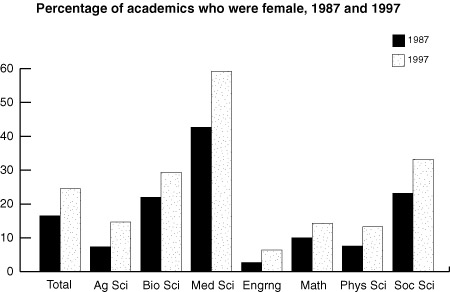

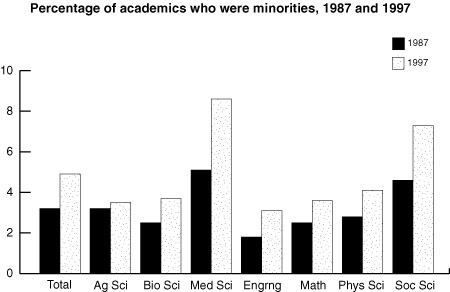

In “Support Them and They Will Come” (Issues, Winter 2000), George Campbell, Jr. makes a compelling case for a renewed national commitment to recruit and educate minority engineers. There is another group underrepresented in the engineering and technical work force that also deserves the nation’s attention: women.

Women earn more than half of all bachelor’s degrees, yet only 1.7 percent of them earn bachelor’s degrees in engineering, compared to 9.4 percent of men who graduate with engineering degrees. Men are three times more likely than women to choose computer science as a field of study and more than five times more likely to choose engineering.

As a result, women are significantly underrepresented in key segments of the technical work force. Women are least represented in engineering, where they make up only 11 percent of the work force. And women executives make up only about 2 percent of women working in technology companies. Rep. Connie Morella likes to point out that there are more women in the clergy (12 percent) than in engineering. There also are more women in professional athletics, with women accounting for almost 24 percent of our working athletes.

Today, creating a diverse technical work force is not only necessary to ensure equality of opportunity and access to the best jobs, it is essential to maintaining our nation’s technological leadership. In my view, our dependence on temporary foreign technical workers is not in our long-term national interest. As we increasingly compete with creativity, knowledge, and innovation, a diverse work force allows us to draw on different perspectives and a richer pool of ideas to fuel technological and market advances. Our technical work force is literally shaping the future of our country, and the interests of all Americans must be represented in this incredible transformation.

We must address this challenge on many fronts and at all stages of the science and engineering pipeline. Increased funding is important, but it is not enough. Each underrepresented group faces unique challenges. For example, women leave high school as well prepared in math and science as men, but many minority students come from high schools with deficient mathematics and science curricula.

The K-12 years are critical. By the time children turn 14, many of them–particularly girls and minorities–have already decided against careers in science and technology. To counter this trend, we must improve the image of the technical professional, strengthen K-12 math and science teaching, offer mentors and role models, and provide children and parents with meaningful information about technology careers. The National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering’s “Math is Power” campaign is one outstanding program that is taking on some of these challenges.

As Campbell notes, we must build a support infrastructure for college-bound women and minorities and for those already in the technical work force. This includes expanding internships, mentoring programs, and other support networks, as well as expanding linkages among technology businesses and minority-serving institutions.

Perhaps most important, business leadership is needed at every stage of the science and engineering pipeline. After all, America’s high technology companies are important customers of the U.S. education system. With the economy booming, historically low unemployment rates, and rising dependence on temporary foreign workers, ensuring that all Americans have the ability to contribute to our innovation-driven economy is no longer good corporate citizenship, it is a business imperative.

KELLY H. CARNES

Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy

U.S. Department of Commerce

Washington, D.C.

Even as our nation continues to enjoy a robust economy, our future is at risk, largely because the technical talent that fuels our marketplace is in dangerously short supply. There are more than 300,000 unfilled jobs in the information technology field today in the United States. Despite such enormous opportunity, enrollments in engineering among U.S. students have declined steadily for two decades. Worse, as George Campbell, Jr. points out, a deep talent pool of underrepresented minorities continues to be underdeveloped, significantly underutilized, and largely ignored.

Our public education system is either inadequate or lacks the resources to stimulate interest in technical fields and identify the potential in minority students. That’s particularly disturbing when you consider that in less than 10 years, underrepresented minorities will account for a full third of the U.S. labor force.

As I see it, two fundamental sources can drive change, and fast. The first is U.S. industry. We need more companies to aggressively support math and science education, particularly at the K-12 level, to reverse misperceptions about technical people and technical pursuits and to highlight the urgency of technical careers in preserving our nation’s competitiveness. More businesses also should invest heavily in the development of diverse technical talent. In today’s global marketplace, businesses need people who understand different cultures, who speak different languages, who have a firsthand feel for market trends and opportunities in all communities and cultures.

The second source is the role model. Successful technical people are proud of their contributions and achievements. Such pride is easy to assimilate and can make a lasting impression on K-12 students. We must encourage our technical stars to serve as mentors to our younger people in any capacity they can. Their example, their inspiration, will go a very long way.

In 1974, IBM was one of the first companies to join the National Action Council for Minorities in Engineering (NACME). We supported it then because we understood the principles of its mission and saw great promise in the fledgling organization. We continue to be strong supporters today, along with hundreds of other corporate and academic institutions, because NACME continues to deliver on its promises. Among them: to increase, year after year, the number of minority-student college graduations in engineering. In times of economic boom or bust, during Democratic or Republican administrations, and when affirmative action is being applauded or attacked, NACME has made a significant difference.

Over the past quarter century, the issue of diversity in our work force–and particularly in our technical and engineering professions–has been transformed from a moral obligation to a strategic imperative for business, government, universities, and all institutions. It’s an imperative on which the future of our nation’s economy rests. The advantage goes to institutions that mirror the marketplace’s demographics, needs, and desires; to those who commit to keeping a stream of diverse technical talent flowing; and to those who take the issue personally.

NICHOLAS M. DONOFRIO

Senior Vice President and Group Executive

Technology & Manufacturing

IBM Corporation

Armonk, N.Y.

The author is chairman of NACME, Inc.

National forests

“Reshaping National Forest Policy” (Issues, Fall 1999) by H. Michael Anderson is an excellent overview of the challenges facing the progressive new chief of the Forest Service, Mike Dombeck, especially his efforts to better protect National Forest roadless areas. One particular slice of that issue presents an interesting picture of what can happen when science and politics collide.

Since the article was written, President Clinton has directed the Forest Service to develop new policies that better protect roadless areas. However, the president deliberately left open the question of whether the new protections will apply to one particular forest: Alaska’s Tongass, our country’s largest national forest and home of the world’s largest remaining temperate rainforest.

Why did he do that? The only reason to treat the Tongass any differently from the rest of the nation’s forests is politics, pure and simple. Chief Dombeck and the President want to avoid angering Alaska’s three powerful members of Congress, each of whom chairs an influential committee.

Indeed, 330 scientists have written to President Clinton, urging him to include the Tongass in the roadless area protection policy. “In a 1997 speech calling for better stewardship of roadless areas,” the scientists wrote to the President, “you stated: ‘These unspoiled places must be managed through science, not politics.’ There is no scientific basis to exclude the Tongass.” Signers of the letter to the president included some of the nation’s most prominent ecologists and biologists, such as Harvard professor and noted author E. O. Wilson; Stanford professor Paul Ehrlich; Reed Noss, president of the Society for Conservation Biology; and Jane Lubchenco, past president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

At the Alaska Rainforest Campaign, we certainly hope that science prevails over politics and that the president decides to protect all national forest roadless areas, including the Tongass.

MATTHEW ZENCEY

Campaign Manager

Alaska Rainforest Campaign

Washington, D.C.

www.akrain.org

Traffic congestion

Your reprinting of John Berg’s and Wendell Cox’s responses to Peter Samuel’s “Traffic Congestion: A Solvable Problem” (Issues, Spring 1999), coupled with recent political events in the Denver area, led me to revisit the original article with more interest than on my first reading. Yet I still find both the original article and the Berg and Cox responses lacking in key respects.

Although there are examples of successful tollways, most have been failures. Market-based approaches work only when there are viable alternatives to allow for market choices. Talk of “pricing principles” and “externalities” is meaningless in cases such as the Pennsylvania Turnpike, where there is no alternative to the tollway. Samuel also ignores the congestion created at every toll plaza. Electronic payment systems do not work well enough to resolve this problem, particularly for drivers who are not regulars on the tollway.

I’m simply mystified by Samuel’s and Cox’s assertion of the “futility” of transit planning given Samuel’s own grudging admission of how “indispensable” transit is in certain situations. Public transit certainly could have helped Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown neighborhood, which was offered a subway stop during the planning of the Metro system. The neighborhood refused the stop and now the major streets through Georgetown are moving parking lots from 6 AM to 11 PM daily. I fail to see how any amount of “pricing discipline” or road building could have changed this outcome.

Mass transit has not always lived up to its promise in the United States, but the failures have almost always been primarily political. Portland, Oregon’s system is a disappointment because the rail routes are not extensive enough to put a significant dent in commuter traffic. Washington, D.C.’s system, although successful in many ways, suffers from its inability to expand at the same rate as the D.C. metropolitan area, a situation exacerbated by the District of Columbia’s chronic funding problems. Both are cases where the political will to build bigger transit systems early on would be paying real dividends now. Compare the D.C. Metro to the subway system in Munich, where more than triple the rail-route mileage serves a metropolitan area of about 1/3 the population of the D.C. metropolitan area. In Germany the political will and funding authority existed to make at least one mass transit system that serves its metropolitan area well.

Finally, I take issue with Cox’s assertion that transit can serve only the downtown areas of major urban centers. Those of us who travel on I-70 from Denver to nearby ski resorts know that traffic congestion can be found far from the skyscrapers. The Swiss have demonstrated that public transit works well in the Mattertal between Zermatt and Visp. Using existing railroad right-of-way between Denver and Winter Park, transit could provide a solution to mountain-bound gridlock.

The key to resolving this nation’s traffic congestion woes lies in keeping our minds open to all transportation alternatives and broadening our focus beyond transportation to include development itself. The lack of planning and growth management have led to a pattern of development that is often ill-suited to public transit. The resulting urban sprawl is now the subject of increasing voter concern nationwide. That concern, reflected in Denver voters’ recent approval of a transit initiative, give me hope that we will be seeing a more balanced approach to these issues in the near future. Such an approach would be far preferable to relying on the gee-whiz technology of Samuel, the sweeping economic assumptions of Berg, or the antitransit dogma of Cox.

ANTHONY B. CRAMER

Fort Collins, Colorado

Hart sorts the major historical figures involved in U.S. science and technology policymaking over the period 1921 to 1953 into five bins. There are the “conservatives,” who hold that the state has no role in science and technology other than guaranteeing intellectual property rights and getting out of the way. Then there are the “associationalists,” who believe that because markets sometimes fail as a result of poor information, we need to create hybrid publicly supported but privately controlled institutions that develop this information and transmit it to the private sector. There are “reform liberals,” who see dangers in the private concentration of economic power and call for the government to step in to regulate or even directly participate in the market.

Hart sorts the major historical figures involved in U.S. science and technology policymaking over the period 1921 to 1953 into five bins. There are the “conservatives,” who hold that the state has no role in science and technology other than guaranteeing intellectual property rights and getting out of the way. Then there are the “associationalists,” who believe that because markets sometimes fail as a result of poor information, we need to create hybrid publicly supported but privately controlled institutions that develop this information and transmit it to the private sector. There are “reform liberals,” who see dangers in the private concentration of economic power and call for the government to step in to regulate or even directly participate in the market. Why then is the public turning away from science? Nay, not just turning away, but fleeing in the opposite direction. My bookcase overflows with wonderful, reductionist accounts of how the world works, written by brilliant scientists for nontechnical audiences–Gould, Dawkins, Sagan, Goodenough–but I look in vain for their names on bestseller lists. Instead, I find such pathetic drivel as Deepak Chopra’s Ageless Body, Timeless Mind: The Quantum Alternative to Growing Old and Harvard psychiatrist John Mack’s Abduction. There is James Van Praagh, Talking to Heaven, while Neale Walsch is having Conversations with God.

Why then is the public turning away from science? Nay, not just turning away, but fleeing in the opposite direction. My bookcase overflows with wonderful, reductionist accounts of how the world works, written by brilliant scientists for nontechnical audiences–Gould, Dawkins, Sagan, Goodenough–but I look in vain for their names on bestseller lists. Instead, I find such pathetic drivel as Deepak Chopra’s Ageless Body, Timeless Mind: The Quantum Alternative to Growing Old and Harvard psychiatrist John Mack’s Abduction. There is James Van Praagh, Talking to Heaven, while Neale Walsch is having Conversations with God. In late 1992, Ashton Carter and William Perry joined John Steinbruner in writing A New Concept of Cooperative Security, a seminal study published by the Brookings Institution. The study’s thesis, subsequently refined in the hefty volume Global Security: Cooperation and Security in the 21st Century, edited by Janne Nolan, was that in the aftermath of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union it was necessary to fashion a new formula for international security based on conflict prevention and cooperation. To a large extent, Carter and Perry’s Preventive Defense represents an extension of that thesis, with reference to a number of key security challenges confronted by the authors during their service in the Department of Defense in the Clinton administration. (Perry was secretary of defense, and Carter was assistant secretary for international security policy.)

In late 1992, Ashton Carter and William Perry joined John Steinbruner in writing A New Concept of Cooperative Security, a seminal study published by the Brookings Institution. The study’s thesis, subsequently refined in the hefty volume Global Security: Cooperation and Security in the 21st Century, edited by Janne Nolan, was that in the aftermath of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union it was necessary to fashion a new formula for international security based on conflict prevention and cooperation. To a large extent, Carter and Perry’s Preventive Defense represents an extension of that thesis, with reference to a number of key security challenges confronted by the authors during their service in the Department of Defense in the Clinton administration. (Perry was secretary of defense, and Carter was assistant secretary for international security policy.) Two interrelated factors have favored nuclear weapons. First has been the driving impulse among many in India’s elites to take actions aimed at transcending the country’s colonial past. Nuclear science and nuclear weapons have been seen as essential in gaining India the respect and standing in international life that it feels it deserves because of its size and ancient civilization. These elites consider the international nuclear nonproliferation regime as “nuclear apartheid,” structured to keep India (and other non-Caucasian countries) out and down. Perkovich shows that it is this “political narrative” and not a “security-first narrative” that has dominated India’s discourse with itself and the world on nuclear issues. To be sure, Indian hawks have cited the security threat from China and, less frequently, from Pakistan as reasons to go forward. But Perkovich richly documents his contrary view that elite hunger for status and recognition have counted for much more.

Two interrelated factors have favored nuclear weapons. First has been the driving impulse among many in India’s elites to take actions aimed at transcending the country’s colonial past. Nuclear science and nuclear weapons have been seen as essential in gaining India the respect and standing in international life that it feels it deserves because of its size and ancient civilization. These elites consider the international nuclear nonproliferation regime as “nuclear apartheid,” structured to keep India (and other non-Caucasian countries) out and down. Perkovich shows that it is this “political narrative” and not a “security-first narrative” that has dominated India’s discourse with itself and the world on nuclear issues. To be sure, Indian hawks have cited the security threat from China and, less frequently, from Pakistan as reasons to go forward. But Perkovich richly documents his contrary view that elite hunger for status and recognition have counted for much more. This is an eminently readable book. When it arrived in my office, I opened it half expecting to find another discourse arguing that we are facing an impending disaster because of chemical effects on or through hormonal systems. I seldom find such discourse engaging. However, the book is primarily a narrative, without polemic, and I found it to be a page-turner (perhaps because of my own involvement in the issue). The first two chapters recount the history of the idea of endocrine disruption and how it rose to prominence. The first section, and indeed the entire book, is peppered with details about the efforts of many of the individuals who have figured prominently in the emergence of this concept. As those familiar with this topic know, Theo Colborn, an environmental scientist currently with the World Wildlife Fund, played a critical role in defining this issue, and her involvement and what led her to the issue are discussed extensively.

This is an eminently readable book. When it arrived in my office, I opened it half expecting to find another discourse arguing that we are facing an impending disaster because of chemical effects on or through hormonal systems. I seldom find such discourse engaging. However, the book is primarily a narrative, without polemic, and I found it to be a page-turner (perhaps because of my own involvement in the issue). The first two chapters recount the history of the idea of endocrine disruption and how it rose to prominence. The first section, and indeed the entire book, is peppered with details about the efforts of many of the individuals who have figured prominently in the emergence of this concept. As those familiar with this topic know, Theo Colborn, an environmental scientist currently with the World Wildlife Fund, played a critical role in defining this issue, and her involvement and what led her to the issue are discussed extensively.