Pathways to the Middle Class: Balancing Personal and Public Responsibilities

Parents are paramount. But government policies targeting specific life stages can help ensure that all children have a good—and equitable—chance on the economic ladder.

The United States defines itself as a nation where everyone has an opportunity to achieve a better life. Correspondingly, everyone should have the opportunity to succeed through talent, creativity, intelligence, and hard work, regardless of the circumstances of their birth. This meritocratic philosophy is one reason why U.S. residents have customarily shown relatively little objection to high levels of economic inequality—as long as those at the bottom have a fair chance to work their way up the ladder. Similarly, people are more comfortable with the idea of increasing opportunities for success than with reducing inequality.

It is critical, then, to identify and employ effective and affordable ways to provide children from every race and every social and income group with ample opportunities to succeed. Here, a considerable body of research points to a variety of promising interventions at various stages of life, from before birth through entry into adulthood.

Who succeeds and why?

One of the ways of thinking about opportunity is in terms of generational improvement in living standards. Among today’s middle-aged population, four in five households have higher incomes than their parents had at the same age, and three in five men have higher earnings than their fathers. The extent to which this will be true for today’s children remains to be seen. More importantly, if everyone grows richer over time, but the economic fates of individuals are bound up in their family origins, then in an important sense opportunities are still limited. If poor children have little reason to believe that they can grow up to be whatever they want, it may be of little comfort to them that they will probably make more than their similarly constrained parents. A better-off security guard may still have wanted to be a lawyer.

The reality is that economic success in the United States is not purely meritocratic. People do not have as much equality of opportunity as society would like to believe, and the United States offers less mobility than some other developed countries. Although cross-national comparisons are not always reliable, the available data suggest that the United States compares unfavorably with Canada, the Nordic countries, and some other advanced countries.

People do move up and down the ladder, over their careers and between generations, but it helps if you have the right parents. Children born into middle-income families have a roughly equal chance of moving up or down once they become adults, but those born into rich or poor families have a high probability of remaining rich or poor as adults. The chance that children born into families in the top income quintile will end up in one of the top three quintiles by the time they are in their forties is 82%, whereas the chance that children born into families in the bottom quintile will do so is only 30%. In short, a rich child is more than twice as likely as a poor child to end up in the middle class or above, according to data presented in 2012 by the Pew Economic Mobility Project.

Why do some children do so much better than others? And what will it take to create more opportunity?

In order to better understand the life course of children, especially those who are disadvantaged, we have developed, along with colleagues at the Brookings Center on Children and Families, a life-cycle model called the Social Genome Model. The model divides the life cycle into six stages and specifies a set of outcomes for each life stage that, according to the literature, are predictive of later outcomes and eventual economic success. The life stages are family formation, early childhood, middle childhood, adolescence, transition to adulthood, and adulthood. The success indicators include being born to parents who are ready to raise a child, being school-ready by age 5, acquiring core competencies in academic and social skills by age 11, being college- or career-ready by age 19, living independently and either receiving a college degree or having an equivalent income by age 29, and finally being middle class by middle age.

The data we use, from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, follow children born primarily in the 1980s and 1990s, starting in 1986 through 2010. We have projected their adult incomes using a statistical model. The projections in childhood and adulthood in our final data set closely track estimates from independent sources such as the U.S. Census Bureau and other surveys.

Among our findings, 60% of the children we followed into adulthood (through age 40) live in a family with income greater than 300% of the poverty line set by the Census Bureau (about $68,000 for a married couple with two children). In short, they have achieved the middle-class dream. This means, however, that roughly 40% have not achieved this success. The reasons are many, but by looking at where children get off track earlier in life, it is possible to begin to see the roots of the problem.

As our data show, about two-thirds or more of all children get through early and middle childhood with the kinds of academic and social skills needed for later success. However, a large portion of adolescents falls short of achieving success even by a relatively low standard. Only a little over half manage to graduate from high school with a 2.5 grade point average during their final year (the only period for which we have data on grades) and have also not been convicted of a crime or become a parent before age 19.

Success is nevertheless more common a decade later. Sixty percent of children will live on their own at the end of their 20s, either with a college degree in hand or with family income of approximately $45,000, which is about 250% of the level at which a family is considered poor. It is roughly equivalent to what a college-educated individual of the same age can expect to earn working full time, according to a 2011 report by the U.S. Department of Education. People in their late 20s without a college degree might achieve this college-equivalent income through on-the-job training, living in a dual-earner household, or by other means.

Putting the adolescent and adult results together, it appears that F. Scott Fitzgerald was wrong. There are second acts in American lives; lots of people make it to the middle class in adulthood despite entering life inauspiciously. But they would almost certainly be better off if they had acquired more skills at an earlier age, and especially if they had navigated adolescence more wisely.

Another way to give meaning to the success probabilities is to look at how success varies by different segments of the population. Consider gender. Boys and girls enter the world on an equal footing, but they take different paths on the way to adulthood. By age 5, girls are much more likely than boys to be academically and behaviorally ready for school. That advantage persists into middle childhood and adolescence. Men catch up in early adulthood and then surpass women in terms of economic success. At age 40, 64% of men but just 57% of women have achieved middle-class status.

The finding that girls do better than boys during the school years is not new. Girls mature earlier than boys and are better able to sit still and follow directions, and thus benefit more from classroom learning at a young age. A number of studies have shown that girls are less likely to act out, drop out of school, or engage in behaviors such as delinquency, smoking, and substance abuse, even as they are more likely to experience depression and face the risk of a pregnancy during adolescence.

Women are not only much more likely to graduate from high school, but they now earn 57% of all college degrees and more graduate degrees, as well. Despite their educational advantages, once they are adults, women still earn less than men. Although this earnings gap has declined sharply during the past half century, women who work fulltime still earn about 80% of what men earn, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce. The reasons for their lower earnings are related to the fact that, mainly as a result of their family responsibilities, women’s labor force participation and hours worked are still lower than men’s, and they are concentrated in occupations that pay less than those held by men. The extent to which these occupational differences reflect social constraints on women’s roles versus their own preferences has been hard to sort out. Single parenthood also accounts for some of the gender gap in adulthood. Single mothers are much more common than single fathers. Even if they work, many single mothers disproportionately bear the burden of feeding additional mouths with their paycheck as compared with noncustodial fathers, whose child support is often modest.

Other patterns of inequality are much stronger. In our study, 68% of white children are school-ready at kindergarten, compared with 56% of African American children and 61% of Hispanic children (although data on Hispanic children were limited). In middle childhood, black children fall farther behind, and by adolescence, both African Americans and Hispanics are far behind white children. By age 30, both are still lagging, although Hispanics have done some catching up. By age 40, a whopping 33–percentage-point difference between blacks and whites persists. Only one-third of African Americans have achieved middle-class status by middle age. Even among those who do reach the middle class, their children are much more likely to fall down the ladder than the children of white middle-class families. The black-white gaps, and to a lesser extent the Hispanic-white gaps, are sizable for both boys and girls, although they are bigger among boys at the start of school and at the end of the high-school years.

If success at each stage varies by gender and race, it varies even more by the income of one’s parents. Only 48% of children born to parents in the bottom quintile of family income are school-ready, compared with 78% of children in the top quintile at birth. The disparity is similar in middle childhood. Perhaps most stunning, only one in three children from the bottom quintile graduates from high school with a 2.5 grade point average and having not been convicted or become a parent. For children from the top quintile, this figure is 76%. Parental income also affects the likelihood of economic success in adulthood, with 75% of those born into the top quintile achieving middle-class status by age 40 versus 40% of those born into the bottom quintile.

Finally, we have examined success rates for children who are born into more or less advantaged circumstances, defined more broadly than by their income quintile. Among children born of normal birth weight to married mothers who have at least a high-school education and who were not poor at the time of the child’s birth, 72% can be expected to enter kindergarten ready for school, whereas the rate is only 59% for women outside of this group. This gap never narrows, and by the end of adolescence, children with less advantaged birth circumstances are 29 percentage points less likely to succeed. At age 40, there is a 22–percentage-point gap between these groups of children in the likelihood of being middle class.

Children born advantaged also retain a large advantage at the end of the next life stage, early childhood. The same pattern prevails for subsequent stages: success begets later success. In middle childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, those who succeeded in the previous stage are much more likely than those who did not to succeed again. For example, 82% of children in our sample who entered school ready to learn mastered basic skills by age 11, compared with 45% of children who were not school-ready. Acquiring basic academic and social skills by age 11 increases by a similar magnitude a child’s chances of completing high school with good grades and risk-free behavior, which, in turn, increases the chances that a young person will acquire a college degree or the equivalent in income. Finally, success by age 29 doubles the chances of being middle class by middle age. In short, success is very much a cumulative process. Although many children who get off track at an early age get back on track at a later age, and can be helped to do so, these findings point to the importance of early interventions that keep children on the right track.

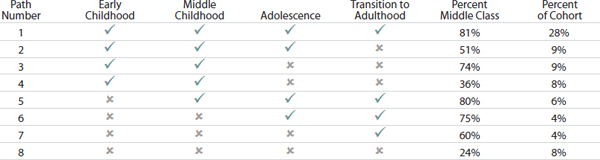

These features of social mobility processes are captured in Table 1, which shows the chance of becoming middle class for eight paths through the transition to adulthood. These are the paths taken by 76% of the children in our sample. The table shows that success in all four stages before adulthood is actually the most common pathway for children to take between birth and age 29, with over one-quarter of children taking that route and 81% of them achieving middle-class status. Of those who fail in all four life stages, a group that is only 8% of our sample, just 24% become middle class by age 40.

Table 1 also shows how early success or failure can matter even among those succeeding in the transition to adulthood. If children consistently fail before succeeding at age 29, they have a 60% chance of being in the middle class at age 40. If they consistently succeed in the earlier stages, they have an 81% chance. Similarly, people failing during the transition to adulthood have only a 24% chance of making it to the middle class if they have a consistent history of failure, but a 51% chance if they have a consistent history of success.

TABLE 1

Probability of reaching the middle class by number of successful outcomes and possible pathways

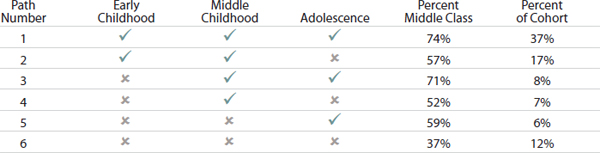

TABLE 2

Probability of reaching the middle class by number of successful outcomes and possible pathways through adolescence

On the other hand, early failures need not be determinative if children can get back on track. Children who are not school-ready have a similar chance of being middle class as those who are school-ready if they can get on track by age 10 and stay on track. Indeed, a striking feature of Table 1 is how well success at age 29 predicts success at age 40. This may be an artifact of the way we define success at age 29. Because it includes having an income of 250% of the poverty level, individuals need only increase their income by about 20% over the next decade to become middle class by middle age.

For this reason, in Table 2 we ignore the transition to adulthood and consider how well particular paths through age 19 predict middle-class status at age 40. These six paths through adolescence cover 88% of the children in our sample, and the two paths involving three consecutive successes or failures account for nearly half of all children. At first glance, success or failure in early childhood seems less important than in subsequent stages. Children who succeed in all three stages have a 74% chance of being middle class at age 40, whereas those who are not school-ready but succeed in middle childhood and adolescence have a 71% chance—essentially no difference. Comparing paths 2 and 4, which are identical except for early childhood, gives a similar impression.

It would be wrong to conclude, however, that early childhood success is unimportant. If the primary way that school readiness affects the likelihood of becoming middle class is by directing people into more successful paths, that fact would be obscured by comparisons such as these. If a child is school-ready, there is a good chance that he or she will continue to succeed in later stages. If a child is not ready, it is relatively unlikely that he or she will get on track. Paths 1 and 2 are much more common than paths 3 and 4; recovery from early failure is relatively rare.

To summarize the data further, we calculated the probability of reaching the middle class by middle age based on the number of life stages in which the individual experienced success. As already noted, an individual who experiences a successful outcome at every life stage has an 81% chance of achieving middle-class status. The probability of achieving this status decreases with each additional unsuccessful outcome. An individual who hits just one speed bump has a 67% chance of reaching the middle class, but this figure drops to 54% if there are two unsuccessful outcomes, 41% with three unsuccessful outcomes, and 24% for those who are not successful under our metrics at any earlier stages in life.

Who are the children who succeed throughout life? They are disproportionately from higher-income and white families, whereas those who are never on track are disproportionately from lower-income and African American families. For example, 19% of children from top-quintile families stay on track throughout their early life, while only 2% of children from bottom-quintile families do. The figures by race show that 32% of white children but only 10% of black children stay on track.

The fact that nearly one-quarter (24%) of our off-track individuals (those failing at every one of our metrics) manages to achieve middle-class status is a reminder that there are quite a few individuals who are economically successful despite a lack of success during school. Such individuals may be successful because of skills or personality traits that are not captured by our metrics, or by relying on support from another family member, or purely by luck.

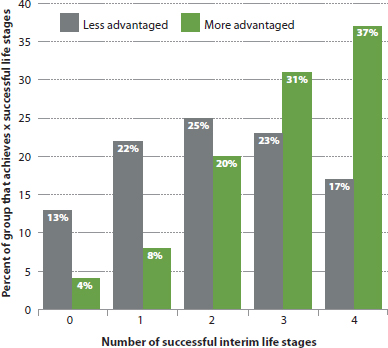

Unfortunately, birth circumstances are highly predictive of the likelihood of achieving success in the four life stages preceding middle age. Children born at a low birth weight or who have a mother who is poor, unmarried, or a high-school dropout—circumstances we denote as less advantaged—have only a 17% chance of achieving all four interim markers of success. Figure 1 shows the likelihood that an individual achieves success at any particular number of life stages conditional on their circumstances at birth.

Although few children from less advantaged backgrounds succeed at every life stage through their 20s, it appears that when they do, they are nearly as likely to reach the middle class as children born into more advantaged families. Figure 2 indicates that children from less advantaged families who stay on track have a 75% chance of joining the middle class, compared with 83% for their more advantaged peers. On the other hand, although additional successes do increase the chances of ending up middle class for disadvantaged children, they often increase the chances more for advantaged children. Advantaged children are about as likely to end up middle class as disadvantaged children who have an additional success under their belt. For example, an advantaged child with no successes through their 20s is nearly as likely to end up middle class as a disadvantaged child with one success. Family background matters because it tends to affect childhood success at each stage of the life cycle, but also because it affects the likelihood of ending up middle class even for children experiencing similar trajectories through early adulthood.

Help on the ladder

Because a number of studies have demonstrated that the gaps between more and less advantaged children are large and getting larger, without a clear plan to prevent the less advantaged from getting stuck at the bottom, the nation risks developing a society permanently divided along class lines. But our results and those of other researchers reveal some good news: Although it may be difficult for many children to stay on track, especially disadvantaged children, birth circumstances do not have to become destiny.

When children stay on track at each life stage, adult outcomes change dramatically. Parents who tell their children to study hard and stay out of trouble are doing exactly the right thing. But government can play a role as well, even if limited. In particular, government at various levels can adopt policies to foster intervention programs targeting every life stage to help keep less advantaged children on track. The research community has now identified, using rigorous randomized controlled studies, any number of successful programs, some of which pass a cost/benefit test even under conservative assumptions about their eventual effects. The following descriptions of successful programs are illustrative, not exhaustive.

Family formation. The first responsibility of parents is to not have a child before they are ready. Yet 70% of pregnancies to women in their 20s are unplanned, and, partly as a consequence, more than half of births to women under age 30 occur outside of wedlock. In the past, most adults married before having children. Today, childbearing outside of marriage is becoming the norm for women without a college degree. To many people, this is an issue of values; to others, it is simple common sense to note that two parents are more likely to have the time and financial resources to raise a child well. Many young people in their 20s have children with a cohabiting partner, but these relationships have proven to be quite unstable, leading to a lot of turmoil for both the children and the adults in such households.

Government can help to ensure that more children are born into supportive circumstances by funding social-marketing campaigns and nongovernmental institutions that encourage young people to think and act responsibly. It can also help by providing access to effective forms of contraception, and by funding teen pregnancy prevention efforts that have had some success in reducing the nation’s high rates of very early pregnancies, abortions, and unwed births. A number of well-evaluated programs have accomplished these goals, and they easily pass a cost/benefit test and end up saving taxpayers money.

Early childhood. The early childhood period is critical, and home visiting programs and high-quality preschool programs, in particular, can affect readiness for school. Home visiting programs, such as the highly regarded Nurse Family Partnership, focus on the home environment. Eligible pregnant women are assigned a registered nurse who visits the mother weekly during pregnancy and then about once a month until the child turns age 2. Nurses teach proper pre-and postnatal health behaviors, skills for parenting young children, and strategies to help the mother improve her own prospects (family planning, education, work). The program is available to low-income first-time pregnant women, most of whom are young and unmarried and enroll during their second or third trimester. It has had impressive success in improving health, such as reductions in smoking during pregnancy, maternal hypertension, rates of pre-term and low-birth-weight births, and children’s emergency room visits, and also appears to affect the timing and number of subsequent births. Children whose mothers participate in the program see modest improvements in their school readiness.

Preschool programs emphasize improving children’s academic skills more than their health or home environments. Preschool attendance is one of the strongest predictors of school readiness. Income and racial gaps in academic and social competencies are evident as early as age 4 or 5, and compensating for what these more disadvantaged children do not learn at home is a highly effective strategy. These programs have an impact not only on school readiness but also on later outcomes. For example, a child who is school-ready is almost twice as likely to acquire core competencies by age 11 and, having achieved those competencies, to go on to graduate from high school and be successful as an adult. Some evidence also suggests that school-ready children go on to do better in the labor market even if their early experience does not affect their test scores in later grades, perhaps because it affects their social skills, their self-discipline, or their sense of control over their lives.

Middle childhood. The period from school entry, around age 5, until the end of elementary school, around age 11, is often overlooked by policymakers. Yet it is the time when most children master the basics—reading and math—as well as learn to navigate the world outside the home.

Scores on math and reading, especially the latter, have improved little in recent decades. Gaps by race have narrowed only modestly, whereas gaps by income have widened dramatically. These academic skills will be much more important in the future as the economy sheds routine production and administrative jobs and demands workers with higher-level critical thinking abilities. For these reasons, almost everyone agrees that the education system needs to be transformed. School reform could include more resources, more accountability for results, more effective teachers in the classroom, smaller class sizes, more effective curricula, longer school years or days, and more competition and choice via vouchers or charter schools.

However, most experts do not believe that more resources by themselves will have much impact unless they are targeted in effective ways. They also agree that accountability is important but must be combined with providing schools the capacity to do better, that teachers are critical but that it is hard to identify good teachers in advance, and that class size (holding teacher quality constant) matters but is a comparatively expensive intervention. Few curriculum reforms have been well evaluated or have demonstrated big effects. Finally, some charter schools and voucher experiments have produced positive results, but charters as a whole do not do a better job than the public schools.

In short, there is no simple solution. Most likely a combination of these or other reforms will be needed to improve children’s competencies in the middle years. Indeed, more-holistic approaches or “whole-school reforms,” such as Success For All, that involve simultaneously changing teacher training, curricula, testing, and the organization of learning have had some success. It is also encouraging that national benchmarks in the form of the Common Core State Standards have now been endorsed by 45 states. The Obama administration has pressed for tracking children’s progress in school, for rewarding teachers based in part on how much children learn, and for more innovation through charter schools. The nation is also going to need new experiments in the uses of technology and online learning. In the meantime, there are numerous more-limited efforts that have had some success at improving reading or math and that could be expanded to more schools.

It is not only academic skills that matter. Our data show that many children lack the behavioral skills that recent research indicates are important for later success. Interventions designed to improve children’s social-emotional competencies in the elementary-school years have produced promising results and need to be part of the solution. Social-emotional learning has five core elements: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decisionmaking. Learning to navigate these areas positively affects children’s behavior, reduces emotional distress, and can indirectly affect academic outcomes.

Finally, our analyses suggest that most children are reasonably healthy at age 11. For those who are not, access to health care is obviously important. It is likely that between Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, most children are (or will be) covered by public or private health insurance. But important exceptions may include illegal immigrants, children who live in rural areas, or children whose parents fail to bring them in for care. In the latter context, a recent experiment in New York City, the Family Rewards program, in which parents were offered a reward for making sure their children had insurance and regular checkups, found that there were only modest effects on the receipt of care, which is already quite high in the coverage area. But making sure that children get dental checkups, immunizations, and other preventive care is worth pursuing.

Adolescence. Our data show that just 57% of children graduate from high school with decent grades and having avoided teen parenthood and criminal conviction. Dropping out of high school, not learning very much during the high-school years, and engaging in risky behaviors are all barriers to later success. There has been a rise in incarceration during the past 30 years, driven by patterns among young men, particularly African American men. In contrast, and further reflecting the diverging trends for young men and women, teen births have declined to historically low levels—a consequence of historically low pregnancy rates, although rates remain high by international standards.

The teenage years have always been fraught with difficulty, but these data should be a wakeup call for parents, schools, community leaders, elected officials, and young people themselves. By the time they are teens, young people should begin to take some responsibility for their futures, and they need to be encouraged by parents and others to do so.

At the same time, school reforms can make a difference. In many studies, high-school dropouts report high levels of disengagement and lack of motivation. Education leaders and policymakers are attempting to respond to these issues of engagement with new types of high schools. One example, from New York City, is the conversion of a number of failing public high schools to small, academically nonselective, four-year high schools that emphasize innovation and strong relationships between students and faculty. The schools, dubbed “small schools of choice,” are intended to serve as alternatives to the neighborhood schools located in historically disadvantaged communities. Admission is determined by a lottery system after students across New York City select and rank the high schools they would like to attend.

The random assignment of students to these schools enabled researchers to study their effect on various student outcomes. The results indicate that enrollment in these schools had a substantial impact on student achievement. Throughout high school, these students earned more credits, failed fewer courses, attended school more dependably, and were more likely to be on track to graduate. They earned more New York State Regents diplomas, had a higher proportion of college-ready English exam scores, and had graduation rates nearly 15% higher than schools examined as controls.

Young adulthood. The transition to adulthood is increasingly lengthy, with more young adults living at home, fewer of them marrying, and more of them continuing their educations well into their 20s or beyond. This makes defining success during this period difficult. We look at what proportion of young adults are living independently and have graduated from college or are in a household with an income above 250% of poverty by the end of their 20s.

One very important barrier to college is inadequate preparation. As our data show, individuals who have graduated from high school with decent grades and no involvement in risky behavior are twice as likely to complete college and have a 71% chance of achieving success by the end of their 20s, whereas those who do not have only a 45% chance. But academic preparation is not all that matters. Research has shown that even among students with equal academic achievements, socioeconomic status has a large effect on who finishes college: 74% of high scorers who grew up in upper-income families completed college, compared with 29% of those who grew up in low-income families. Moreover, these income gaps in college attendance have widened in recent years.

There are a multitude of federal and state programs, tax credits, and loans that subsidize college attendance. One of the most important for closing gaps between more and less advantaged children is the Pell Grant program, because it is targeted to lower-income families (those with incomes below about $40,000 a year). The federal government spends about $36 billion on the program annually. The evidence on the effects of the grants is somewhat mixed. In part, this is because even if financial incentives matter (and they appear to, according to the best research), the process of applying for grants is daunting for lower-income families. Ongoing reforms to simplify the process should help. It has been estimated that for each additional $1,000 in subsidies, the chance of college enrollment increases by about 4 percentage points.

Whether enrollment leads to graduation is another matter. Although enrollment rates in postsecondary institutions, including community colleges, have shot up, graduation rates have increased very little. Efforts to improve retention and graduation rates by coupling tuition assistance with more personalized attention and services have had only modest effects to date.

Adulthood. Once individuals have completed schooling, left home, and entered the work force, the most important determinant of their success is the labor market. For those who reach adulthood without the academic and social skills to enter the middle class on their own, government policies should be linked to personal responsibility and opportunity-enhancing behaviors. This includes education subsidies tied to academic performance; income assistance that encourages and rewards work, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit and child-care subsidies; career and technical education tied to growing sectors of the economy; and more apprenticeship and on-the-job training. Although important for all people during this aftermath of the Great Recession, such programs may be especially important for less-well-educated individuals, who have suffered not just a loss of employment opportunities but a decline in their earnings.

Putting the full responsibility on government to close all of these gaps across all of the life stages is, of course, unreasonable. But so is a heroic assumption that everyone can be a Horatio Alger with no help from society. By drawing on the lessons of science, government can put in place effective programs to boost the success of everyone striving to reach the middle-class dream, while also saving taxpayers money over the long run.